The

Mystery Behind Waheed Murad

The

Mystery Behind Waheed Murad

Dawn, Images,

November 23, 2008

By Khurram Ali Shafique

I have been researching the life and

works of Waheed Murad (1938-1983) for more than 20 years now and

the mystery around him deepens with every new clue that I come

across.

He is the greatest screen legend

of Pakistani cinema and therefore we forget that he was also

a writer, director and producer who entered filmdom with the

intention of making some serious statements about the nation

(he didn’t even appear on screen in his first two productions).

As soon as we shift our attention from the Chocolate Hero

to the film-maker, we are in for a volley of surprises. Here

I discuss just one of the many.

As an actor Waheed Murad featured

in more than 120 films but he also produced 11 titles under

his banner, Film Arts. The first two in which he didn’t

appear may rightly be regarded as pilot projects since he

hadn’t even formed his team by that time, and it can

be presumed that the statement he was trying to make didn’t

come across effectively. That leaves nine films which can

be rightly considered as his “statements”. Quite

surprisingly, they seem to depict the gradual unfolding of

a single profound message — sometimes too bold to be

given directly and hence necessitating the use of masks and

parables.

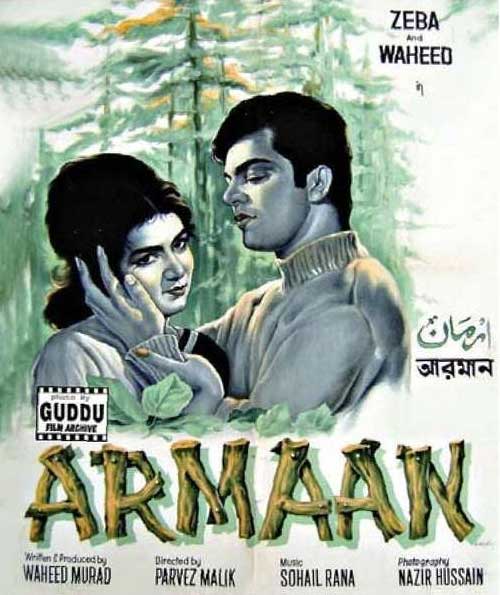

'Armaan of a Nation': a

study of the movie Armaan (1966) by Khurram

Ali Shafique published in Dawn Images, March 2010. |

|

The first is Heera Aur Patthar

(1964), the story of two brothers from a working-class family

on the outskirts of Karachi. One of them gets educated in the

city but in order to marry in a wealthy family he disowns his

ageing father, ry of an orphaned boy raised by a benevolent family

falling in love with a young widow already the mother of a school-going

daughter.

I see a definite pattern emerge here.

If the torn-apart family in Heera Aur Patthar is taken

as an analogy of Pakistani society then the message is clear —

the educated middle class has severed its organic connection with

the unschooled masses who are compelled to drive the wheels of

the country all by themselves (the disowned brother is a donkey-cart

driver played by Waheed).

If this was indeed the message

that Waheed intended to impart through the film, then the

very next one suggests the solution: Educated youth from well-off

families should try to find out what their real ideal ought

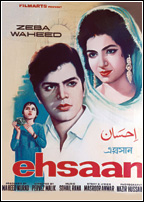

to be. Ehsaan (1967) seems to present the basic principle

on which societies like Pakistan can be built. The principle

is ehsaan which, roughly translated, means ‘benevolence’

but has a deeper meaning in sufi terminology and these meanings

are successfully explored by the gifted poet Masroor Anwar

in the film’s songs and dialogue.

As a filmmaker presenting the anatomy

of Pakistani society through his films, he couldn’t remain

indifferent to the rift between West and East Pakistan which had

begun to appear by that time. It became the theme of his next

film which was symbolically named Samandar (1968), since

the sea and not the land connected the two wings of the then Pakistan.

For the female lead role he invited the Bengali actress Shabnam

from East Pakistan who had never worked in West Pakistan before.

The music was also composed by

Deeboo Bhatachariya (instead of Waheed’s usual composer

Sohail Rana). The lyrics were penned by none other than Sehba

Akhtar who later became famous as the Poet of Pakistan for

patriotic numbers such as 'Main Bhi Pakistan Hoon, Tu Bhi

Pakistan Hai'. In the lyrics for Samandar, he infused the

same patriotism in layers of allegory, such as the famous

title song 'Saathi, Tera Mera Saathi Hai Lehrata Samandar'

(O’ friend, the sea is our mutual friend).

'The Parable of

the Sea': a study of the movie Samandar

(1968) by Khurram Ali Shafique published in Dawn Images,

November 2010. |

|

Interestingly, the story of Samandar

shifted the focus from love interest to the strained friendship

between two friends. Set in a fishing colony which can be treated

as an analogy of Pakistan, one friend aspires for nothing except

love while the other who aspires to become the next leader of

the fishing colony ends up playing in the hands of outsiders.

The first friend (Waheed) is persuaded by the people to defeat

the other in the race for leadership, but having done that he

transfers the power to his defeated friend after eliciting from

him a promise that he would serve the community without playing

into hands of the outsiders.

In those days Samandar

was not taken as anything but an ordinary film, but now it

seems almost certain that it was an analogy of the East Pakistan

crisis: Waheed was suggesting that the only moral ground for

asking the East to give up on the Six Points for the sake

of the federation was that the politicians of West Pakistan

should agree in return to let the next prime minister be from

the East. It may be asked why Waheed didn’t elaborate

his message so that people could understand what he was trying

to say. This is a question which should answer itself. Those

were the days when Sheikh Mujibur Rehman was being tried for

treason by a military government and what Waheed was saying

about the issue could have landed him in jail and earned a

permanent ban on his film.

Quite understandably, the next

was Ishara (1969), literally meaning ‘hint’

or ‘suggestion’. It is the only film ever directed

by Waheed (he also wrote it) and turned out to be an allegory

about the film-maker’s creative self. The film opens

with the subjective camera moving into an alley, and Waheed’s

voiceover telling us that this is the street where he lives.

Thus the camera becomes the eye of the viewer visiting the

inner world of Waheed’s creative self (he plays a painter

whose paintings are “admired by many but purchased by

none”).

Quite interestingly, we see him

entertaining three little children in his studio. He asks

their opinions about his newly finished painting, and the

opinions turn out to be very immature. Here is Waheed and

his audience then. He has got no option but to wait for the

day when they “grow up” but even while they are

immature, his affection for them is unfailing.

Naseeb Apna Apna (1969)

takes this analogy into a darker zone by portraying a sister

who works as a dancing girl in the red light area in order

to “educate” her brother who lives in a hostel

and is unaware of the dark side of his family. Needless to

say the dancing girl can be taken as an analogy of the entertainment

industry which is unfairly treated as a mere plaything (a

point which Waheed’s team of Pervez Malik, Sohail Rana

and Masroor Anwar were also trying to drive home in another

film called Doraha around the same time).

The East Pakistan crisis is revisited

in Mastana Mahi (Punjabi), which was released in early

1971. Sheikh Mujib had won the elections but the politicians of

West Pakistan as well as the army were reluctant in transferring

power to him. Failure of negotiation was followed by a disastrous

army action which resulted in the break up of the country.

The opening sequence of Mastana

Mahi was about a village thug who prevents a married woman

from going to her husband belonging to another village. In retrospect,

allusions to the political situation are extremely obvious throughout

this sequence (such as the skin of a Bengal Tiger displayed on

the wall of the village thug although the tiger is not found in

Punjab), and the rest of the film places the question of national

integration in its larger perspective — and it is a perspective

which is relevant even today.

Waheed’s last two films,

Jaal (1972) and Hero (1985), although separated

by 13 years (the last film was released more than a year after

his death), have the common theme of the agonies of a soul

which knows too much. Jaal’s poor taxi driver educates

his sister and gets her married into a well-to-do family.

While raising money for that purpose he falls into the trap

of a crime racket which, he learns only at a later stage,

is being run by none other than the father-in-law of his newlywed

sister. For her sake he is willing to risk all but she risks

her own life in order to force him to speak the truth. Hence

we see a complete reversal of the Heera Aur Patthar

situation as things come full circle and for the better.

Waheed had claimed before the press

that “A new Waheed Murad will appear before you in Hero.”

It is the story of a thief who is so perfect in his craft

that he leaves no trace behind (just as Waheed doesn’t

leave any clue of the underlying subversive messages in his

films, and yet they could not be more perfect in allegorical

structure). This becomes his Achilles’ heel because

he gets caught every time the police don’t find any

evidence on the scene of the crime. His boss provides him

cover by setting up a fake film company and introduces an

illiterate look alike of the thief as a hero. The police mistake

him for the thief and maintains surveillance on his activities

while the real thief goes about his business — he now

has an alibi.

Needless to say, the story was

written by Waheed himself. This leaves us with a nagging question

about who the real Waheed Murad was: the one we watched on

screen as the Chocolate Hero or the genius who stayed behind

in the dark and played around with our emotions? In one of

his last interviews he had said, “Sometimes I think

that if I suddenly disappear or am no more for any reason,

I would like to be remembered by the song ‘Bhooli

hui hoon dastaan, guzra hua khayal hoon/ Jiss ko na tum samajh

sakay mien aisa aik sawal hoon’.” (I’m

a tale forgotten, a thought bygone. I’m the question

which you couldn’t understand).