Search the Republic of Rumi |

|

DAWN The Review, December 25-31, 1997 " People who say that musical film is the only genre Pakistani cinema has produced are actually forgetting that Pakistan has brought a huge number of documentaries. Some of them have been acclaimed internationally as the best. It would surprise some people today, but not those with a good memory, to say that the best documentary ever produced on Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib was a Pakistani documentary. Researched, written and directed by our ace documentarian Khalique Ibrahim Khalique it was an 80 minute long colour documentary on 35mm produced by the Department of Films and Publications in 1971. Khalil Ahmad provided the musical score based on the ragas that were common in Delhi during the age of Ghalib.

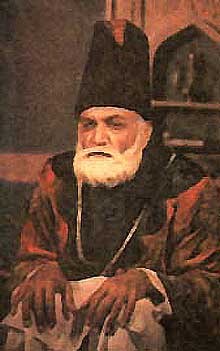

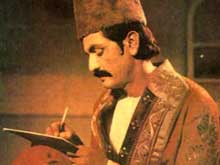

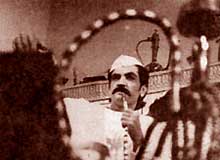

Ismat Chughtai was once asked by Kaifi Azmi in India to compare his documentary on the same subject with the one made by Khalique, as she had had the occasion to watch it on one of her trips to Pakistan. In her characteristic blunt manner she came out with "What comparison between heaven and earth", or something like that. Kaifi and his wife were obviously taken aback. Later, when they watched Khalique’s Ghalib for themselves Mrs. Kaifi helplessly exclaimed: "Ismat was not exaggerating." Ghalib was commissioned by the Ghalib Centenary Committee headed by Prof. Hameed Ahmad Khan of Punjab University in 1968. Due to lack of official support except from such literary minded bureaucrats as Altaf Gauhar, Aftab Ahmad Khan and some others. It could not be completed before 1971. Only five copies on 35 mm could be sanctioned and none on 16 mm. One of the copies was sent to the Tashkent Film Festival where it arrived late (thanks to the efficiency of our bureaucracy) but it still managed to gain popularity in the former USSR – partially because of the socio-economic interpretation of the poet’s life and thoughts so excellently accomplished in this film. The Library of Congress commissioned an extra copy for their own collection. In Pakistan it could not be released to a larger audience due to its length. It was shown in some colleges and there were a few special screenings for a selected audience. Those who have mentioned it in their own writings include Sahar Ansari, Safdar Mir and Hameed Ahmad Khan. And then, just as all good things come to an end, especially if the Government of Pakistan is the sponsor, this jewel was also wrapped in the notorious dubba and thrown by the Department of Films and Publications into some cellar to gather dust – which could be fatal for something made out of celluloid. Today, the only known copy is the one that Mr. Khalique had fortunately kept in his own house, but he too is afraid of handling it himself. One other film that he had kept in the same place has already turned into molten wax and he is not quite sure what shape Ghalib would show if its box is opened today. What I had a chance to see was a shadow of the original masterpiece. It was a role print on VHS taken more than ten years back. It had lost its wonderful colours but even so it was sufficient enough to give me the impression that I am witnessing one of the greatest documentaries ever produced in the history of motion picture anywhere anytime (and that I am saying without allowing grace marks for its low budget of Rs. 85,000 or the out-of-date equipment that was used for its making.) The thesis of the film is that Mirza Ghalib was a poet born ahead of his times. He absorbed the richest essence of his own culture as well as taking a glimpse of the modern western civilisation during his brief visit to Calcutta in 1828-9. This has been translated into the form of a documentary through original artefacts of those times, including documents, furniture, ornaments, still pictures, etc. Most of these artefacts did not only belong to the days of Ghalib but actually belonged to him or his friends. That all this material could be found in Pakistan is an amazing feat in itself and speaks volumes about the dedication of the filmmaker. Not a single shot in this film was lifted, and virtually every single frame was filmed in Pakistan – and that includes a moving shot of Taj Mahal! Actors and models were used for this film within the limits prescribed by the Declaration of the World Union of Documentary. The issue for portraying Ghalib, therefore, was not just that the actor should resemble the real man but also that he should portray the exuberance of intelligence that an extra-ordinary genius like Ghalib could have possessed. Subhani Bayounus, who, in the comedy of Khwaja Moeenuddin had earlier succeeded on the first count and failed on the other, was selected by Khalique to succeed on both in the case of this documentary. And one cannot resist adding that the performance given by Bayounus in this documentary has not been matched by anyone else in that role – even Naseeruddin Shah falls miles behind. The long solo shot introducing him as Ghalib succeeds in capturing the near-supernatural intelligence and the contradictory features of frankness and restraint that constitute our mental image of Ghalib. Through a tactful handling of light, shade, camera angle and the skills of the actor himself this effect has been achieved and retained through the three distinct phases of the poet’s life. Up to the age of twenty-five we see him as a spoilt young man given away to the pleasures of the flesh and tastes but also capable of producing poetry that stands out above his contemporaries. The next stage of his life is the age of his great Persian verses when he is sobered down and alleviated to philosophical contemplation primarily through two major influences of his life: the tragic love affair with a high-class beauty (but not a prostitute, as suggested by most other film-makers) and his visit to Calcutta, the show-window of the British civilisation in India. The third and final phase begins around the age of fifty when he is treacherously imprisoned on the charge of gambling. Out of the shame of being convicted (and this is Mr. Khalique’s own thesis) arises in Ghalib an awareness of the superficiality of the feudal culture. Ghalib’s transformation from one of the many pleasure-loving elite of the decadent Delhi to the prophet of a new age was never more succinctly presented in print or in visual. The visual interpretation of 39 Urdu and 12 Persian couplets from Ghalib, and through them of his idea of beauty, only help achieve this end – even though it raised a small controversy when the film was first released. "What is the future of what is almost certainly the best documentary Pakistan produced?" To this Mr. Khalique replies with the imperfect indifference of an artist who has finished his job: "Some friends are talking about screening it after the month of Ramadan, to commemorate the bi-centenary of Ghalib’s birth. Maybe if the celluloid is still in good shape…" |

"What is the future of what is almost certainly the best documentary Pakistan produced?" |

|||||||||

Awaiting an Audience

Awaiting an Audience