Search the Republic of Rumi |

|

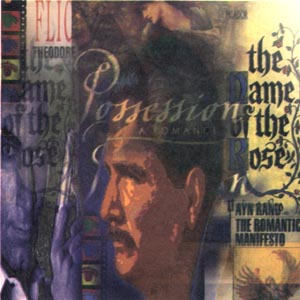

THE HERALD, March 1998 "The New Romantics  What do Allama Iqbal, lan Fleming, Doris Leasing, Ayn Rand, Ibne Safi and Idries Shah have in common? Odd as it might sound, these writers were all pleading the case of romanticism at a time when classicism reigned supreme. During the twentieth century, colonial education made if possible for writers across the globe to find inspiration in the same texts and write in response to each other. As a result authors writing in this century adhered more or less to the same spirit despite differences of attitude and style. The spirit that dominated their work was classicism, characterized by a focus on reality rather than imagination, an appeal to reason rather than feeling, a concern for meticulous detail and references to other writing of the past and the present. However, one international group of rebels chose to neglect the spirit of the day. This club comprised writers of varying stature, from acclaimed modern masters to authors of popular bestsellers. Their literature was rooted in the nineteenth century romanticism, characterized by the larger than life portrayal of human beings, not as what they are but rather as what they might be and what they ought to be; an unfailing optimism, which viewed the world as a place worth living in and worth dying for, expressed primarily through images and metaphors of beauty; and an insistence that moral values, whatever they might be, must be cherished and glorified. More often than not, Nieztsche seems to have been a dominant influence on the romantics of our century. To place Allama Iqbal, lan Fleming, Doris Lessing, Ayn Rand, Ibne Safi and Idries Shah together in the same club might at first appear implausible. After all, their writing belonged to wholly different genres. Moreover, they wrote in different languages and belonged to different cultures. Nor were they writers of equal literary stature. The link between them appears even more tenuous when one considers the fact that some members of the club of twentieth century romantics had not even heard of each other. But then, such a seeming paradox is characteristic of the literature of this century, where one can no longer speak in isolation about authors from different cultures. They might not have read or known each other, but they have almost certainly all grown up on the same books. As such, their paths crossed and intertwined, as did the ideas and concerns that dominate their work. What binds these writers together more than anything else is their common outlook towards the dominant literature of the twentieth century, which Iqbal anticipated as far back as 1908. He feared that the defeat of the writer's imagination at the hands of scientific thought and technology would produce "a literature of despair." Consequently, he dedicated his life to writings steeped in romantic ideals. Ayn Rand, born in Russia in 1907, grew up to see a blossoming of the kind of pessimistic literature Iqbal had predicted. It is unlikely that she had ever read Iqbal, but she was clearly inspired by many of the same sources. In 1965, moreover, she condemned modern literature in words that could well pass for a translation of a passage from Iqbal's Zarb-i-Kalim: "Fear, guilt and the quest for pity combine... to justify and rationalize the artists' own feelings. To justify a chronic fear, one has to portray the existence of evil; to escape from guilt and arouse pity, one has to portray man as impotent and innately loathsome... Hence the frantic search for misery and descent from compassionate studies of alcoholism and sexual perversion to dope, incest, psychosis, murder, cannibalism." While established writers of 'high literature' were busy producing the literature of despair, a number of so-called 'low-brow' authors created a new genre — the spy thriller. We cannot say how Iqbal would have responded to this type of novel (even though we know he was an avid admirer of the Arabian Nights) but Ayn Rand categorically described spy thrillers as "the last remnants of Romanticism" and considered them to be superior to most of the 'high literature' of her time. Writing in defense of lan Fleming's ]ames Bond, she Insisted that such thrillers upheld the romantic ideal of "purposeful action in pursuit of values." What she wrote is equally true or another writer in this genre, Ibne Sati, and his much underestimated spy fiction. Ibne Safi, the Pakistani author of Imran Series and Jasusi Duniya, belongs to the same club. Inspired less by Nieztsche and more by lqbal, many of his prefaces are well-written, meaningful treatises in defense of romanticism. His 246 novels are no farther from the spirit of Iqbal than Ian Fleming's James Bond was from the spirit of Ayn Rand. Once, pleading for the freedom of the novelist to imagine things that may seem far-fetched, he quoted a Russian newspaper which reported the Invention of a certain robot. This report appeared about seven or eight years after Ibne Safi himself first imagined such a machine in one of his novels. "What I am saying is not to suggest that the Russians lifted the idea from my book," Ibne Safi wrote. "What I mean to say is that a single thought can find place at the same time in the mind of a storyteller and a scientist. The storyteller paints a pen picture whereas the scientist materializes it in the real world " Now compare this passage with the words of Doris Lessing, who wrote several years later in The Memoirs of A Survivor: "I 'invented' an animal that was half-cat and half-dog and then read that scientists were experimenting on this hybrid. . . Yes, I do believe that it is possible, and not only for novelists, to 'plug in' to an over-mind, or Ur-mind, or unconscious, or what you will, and mat this accounts for a great many improbabilities and 'coincidences'. " Doris Lessing's preface is obviously written in a more optimistic mood than the scathing notes of Ayn Rand some 15 years earlier. This is perhaps because of a style of literature which began to emerge during her day, an imaginative literature written by authors with a good working knowledge of the physical sciences. This trend was most explicit in science fiction dealing with outer space, and gave Doris Lessing a reason to believe that imagination would soon triumph over technology: "It is by now commonplace to say that novelists everywhere are breaking the bonds of the realistic novel because what we all see around us becomes daily wilder, more fantastic, more incredible." This statement is all the more interesting because, with these words, we observe the history of literature coming full circle. Just as Iqbal had predicted the onset of classicism, Lessing anticipated the rebirth of romanticisim. The last two decades have in fact witnessed an unleashing of romantic energy from some of the best literary minds of our age, generating a significant revival of the romantic tradition. This can be seen in such books as Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose (1980), A. S. Bayatt's Possession (1990), Theodore Roszak's Flicker (1991) and Donna Tartt's The Secret History (1992). Novels such as these (and more are being written every day) celebrate the romantic ideals of magnificence and heroism. These writers — and one may call them the New Romantics — will probably set the mood that will dominate world literature in the years to come. This type of literature had been actively discouraged by the pundits of literary criticism throughout this century. Anyone writing in the romantic mode had to be as "good" as lqbal, Ayn Rand or Doris Lessing, or be prepared to be damned as cheap. By the same token, anyone writing the literature of "fear, guilt and pity" could be as "bad" as Fleming or Ibne Safi and still be recognized as 'being Kafka-ish'. As a result throughout the twentieth century, thrillers, romances and other kinds of popular bestsellers were excluded from the ranks of 'high literature'. But the New Romantics have finally come of age, and have actually managed to outdo the classicists in classicism: while the average reader is engrossed in a thrilling cloak and dagger plot, the informed critic is astonished by the author's display of hard-core knowledge of various academic discipline? The Name of the Rose, for instance, might well be a medieval James Bond thriller, but a high-brow critic will be impressed by the writer's erudition. Similarly, the author's mastery of literary criticism is clear in Possession, apart from the novel's high-tension detective plot. Flicker, meanwhile, could not have been written without a thorough knowledge of the philosophy of cinema. Just as The Secret History required a solid grasp on the literature of the ancients — the opening of this thriller about a mysterious murder at a university campus grips the lay reader and the classics aficionado alike: "Does such a thing as 'the fatal flaw', that showy dark crack running down the middle of a life, exist outside literature? I used to think it didn't. Now I think it does. And I think that mine is this: a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs." Perhaps the most amazing product In the showcase of New Romanticism is Jolstien's Sophie's World, which serves as a textbook of pure philosophy and well as a readable yarn. Given this blossoming of a new kind of literature, we might well be witnessing the birth of a New Romantic era. If so, the importance of the lonely romantics of the twentieth century will now become clear. Authors such as Iqbal, Ayn Rand and Doris Lessing, as well as Ibne Safi and lan Fleming, were writing in the shadow of nineteenth century romanticism and attempted to apply its principles to their work in an antagonistic environment. However, what they have written may now serve as a bridge between the Romantics of the previous century and the New Romantics that are beginning to emerge. Similarly, the collage format that Idries Shah adopted to communicate a bulk of Sufi philosophy might well become a popular and sensible manner in which to discuss literary theory and history in such times as ours when literary material is so profuse and diverse that the old fashioned essay style of academic writing might soon become inadequate as a method of analysis. If the critical and commercial success of writers in our club of New Romantics is any Indicator, it is clear that in the next century, the term 'high literature' will encompass interesting literature and thrilling literature. Just as second-rate exercises in literature of guilt and pity flourished in the age of Albert Camus, the times of Umberto Eco and Donna Tartt may see the thriller emerge from the shadow of disrepute that hung over it through most of the twentieth century. While speaking of the New Romantics and texts such as Possession and The Name of the Rose, it must be acknowledged that such novels have not been written in our part of the world so far. But it seems certain that something along similar lines will appear soon, simply because the world today insists on being one. In fact, what is certain about the literature of the next century is that it will be a 'world literature'. With the communication explosion of the late twentieth century, distances between writers in different parts of the world has shrunk immensely. Today, thanks to satellite television and the Internet, a writer sitting in a middle class locality in Karachi may end up more emotionally moved by an event thousands of miles away, such as the funeral of Lady Diana, than by an incident on the ground floor of their own apartment block. In the decades to come, this distance is only likely to shrink further. As such, in the near future, it will become all the more important lo consider writers all over the world to be part of a common pool of human intellect. If the twentieth century made It possible to speak in terms of world literature, the twenty-first will make it impossible to speak in any other terms. The challenge for the future, however, is for literature to perform that most complex of all tasks: going back to the simplest basics. |

The Last two decades have witnessed an unleashing of romantic energy

from some of the finest literary minds of our age. Khurram Shafique reads between the lines to discover that if the twentieth century made it possible to speak in terms of world literature, the twenty-first will make it impossible to speak in any other terms.

|

||