| DAWN, Books &

Authors November 4, 2007

The Inevitable Destination

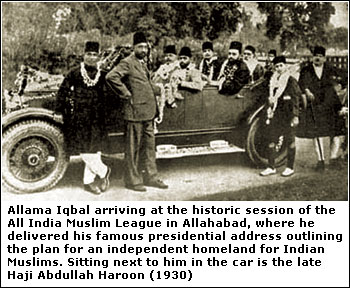

Pakistan has one of the richest

foundational documents in the world. It is the presidential

address delivered by Dr Sir Muhammad Iqbal at the annual

session of the Muslim League in Allahabad in December 1930.

So far the document has only been studied from the perspective

of political science and obviously such studies ignore the

literary aspects of the text. An alternate study of the

Allahabad Address (as it is popularly called) can

be rewarding and may bring out some futuristic aspects of

this national treasure.

For instance, here are the two famous two sentences (italicised

by Iqbal himself), which every school-going child in Pakistan

recognises very well:

‘I would like to see the Punjab, North West Frontier

Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single

state. Self-Government within the British Empire, or without

the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North-West

Indian Muslim state appears to me to be the final destiny

of the Muslims at least of the North-West India.’

It may be noticed that the same thing is being said in each

sentence but the second sentence is more detailed. Since

that detail could have been included in the first sentence

itself and Iqbal as a wordsmith was especially known for

compactness, this ‘redundancy’ cannot be without

a reason. This is where stylistics comes in. We see that

the first sentence is a wish (‘I would like to see…’)

while the second is information (‘appears to me to

be the final destiny…’). Iqbal’s wish

is only to see the four provinces amalgamated into a single

state (as they are now in the shape of the present-day Pakistan).

However, ‘the final destiny’ of his people holds

some open possibilities, and which ones of these materialise

depends on how people react to events and the choices they

may make.

The ‘self-government’ of Muslims could occur

‘within the British Empire, or without the British

Empire.’ Leading Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal

has shown in her study of Jinnah, The Sole Spokesman (1985),

that right up to 1946 both options were open to the people

of India. Hence Iqbal worded his statement in a way that

could accommodate either possibility.

This self-government is the destiny, ‘at least’

of the Muslims of North-West India. The phrase ‘at

least’ has also revealed its significance since East

Bengal joined the federation of Pakistan at one time and

seceded afterwards. The future of Kashmir also remains undecided

as yet. But North-West India has remained self-governing

as the state we know as ‘Pakistan’, and hence

the phrase ‘at least’ is most appropriate.

Hence, while informing his audience about ‘the final

destiny’ or the future events of history he structures

his sentence in a manner that could include all the possible

‘ifs’ of history. Indeed, this is a very extraordinary

manner of making a political statement but if we list the

major theme of each section of the document we find that

this extraordinary statement is not hanging in midair but

in fact the whole document is carefully woven around it.

Quite frankly, it is something which we need to understand

if we care to know why Pakistan was conceived or if we are

curious about its destiny in the world.

Iqbal says at the very opening, ‘I lead no party;

I follow no leader.’ Instead, he says, he has given

the best part of his life to a careful study of Islam and

has developed, he thinks, ‘a kind of insight into

its significance as a world-fact.’ Then comes the

first section, ‘Islam and nationalism’, where

he admits that he is going to discuss things only from the

point of view he has already expressed in the opening lines.

From this point of view, ‘Man is not the citizen of

a profane world to be renounced in the interest of a world

of spirit situated elsewhere.’ Matter and spirit are

essentially a single unity and we ought to take a holistic

approach towards issues.

The second section, titled

‘The unity of an Indian nation,’ defines the

role of spirituality from the holistic perspective established

earlier. From this point of view, the highest order of spiritual

experience cannot be completely ascetic. ‘It is individual

experience creative of a social order,’ says Iqbal.

Hence spirituality requires the formation of a society where

each religion becomes supportive of other religions. Referring

to the non-Muslims he says, ‘Nay, it is my duty, according

to the teachings of the Quran, even to defend their places

of worship if need be.’ This is what he calls in another

writing a ‘spiritual democracy.’

The third section is ‘Muslim India within India.’

It is here that he proposed, as a practical step towards

achieving this spiritual democracy, a Muslim state in North-West

India. As we have already seen, it is more than wishful

thinking. It is an opinion pragmatically based on the expected

direction of future events. The ‘wish’ he is

making is the best way of utilising the possibilities embodied

in those future events.

In the fourth section, ‘Federal States’, he

points out a misunderstanding about the principle of nationality.

The Congress understands the word nation to mean ‘a

kind of universal amalgamation in which no communal entity

ought to retain its private individuality,’ he observes.

If spirit and matter are one (as established earlier) then

the error of this approach becomes self-evident.

The fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth sections, ‘Federation

as understood in the Simon Report’, ‘Federal

scheme as discussed in the Round Table Conference’,

‘The problem of defence’ and ‘The alternative’

comprise of an analysis of the British India and establish

the fact that democracy and communal identities should not

be separated from one another. The proposed Muslim state

is a good way of achieving that end, and in the ninth section,

‘Round Table Conference’ he describes such a

state as a practical step towards ‘a final combination

of humanity’.

The leaders required for such

a task are persons who, ‘by Divine gift or experience,

possess a keen perception of the spirit and destiny of Islam,

along with an equally keen perception of the trend of modern

history.’ Paying attention to the finer details of

the document we do not find such a statement to be out of

place by the time we arrive at it in this last section.

The Allahabad Address takes us into an intellectual

atmosphere where leaders who have an insight into the future

are a plausible thing. Since the destiny of Islam, according

to him, is something that can be predicted to a great extent,

the ‘Conclusion’ of the document suggests that

‘at critical moments in their history it is Islam

that has saved Muslims and not vice versa.’ By Islam,

he means more than a set of social norms. He means an insight

into what twists and turns life is going to take in its

onward march towards ‘a final combination of humanity.’

That final combination, where

a holistic approach becomes the rule of life, is the inevitable

destination of humanity although the way to it may be rough

and strewn with mishaps.

|