|  New

Discoveries About The Reconstruction of Religious Thought

in Islam New

Discoveries About The Reconstruction of Religious Thought

in Islam

Khurram Ali Shafique

IQBAL REVIEW - Journal of Iqbal Academy

Pakistan. April 2007; Volume 48, Number

2. Editor Muhammad Suheyl Umar. Published by Iqbal Academy

Pakistan, Lahore

Introduction Introduction

The

Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam is seen

as a problematic writing of Iqbal. The reason may be that

although much has been written about the book, it has never

been subjected to a linguistic analysis. That is what I

intend to do in this paper along with a comparative study

of this book with two others writings of Iqbal written around

the same time. The “new discoveries” in the

title of this paper refers to some astonishing features

of the Reconstruction that come to light when such

a study is carried out. These features have not been brought

to light before. The

Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam is seen

as a problematic writing of Iqbal. The reason may be that

although much has been written about the book, it has never

been subjected to a linguistic analysis. That is what I

intend to do in this paper along with a comparative study

of this book with two others writings of Iqbal written around

the same time. The “new discoveries” in the

title of this paper refers to some astonishing features

of the Reconstruction that come to light when such

a study is carried out. These features have not been brought

to light before.

In December 1924, Iqbal delivered a lecture

on ijtihad in Lahore. Its text is now considered

to be lost. It raised some criticism locally but was much

appreciated in South India where the Madras Muslim Association

invited Iqbal to deliver a series of lectures. He started

preparation in the summer of 1928 and delivered the first

three lectures in Madras and Hyderabad Deccan in early 1929.

Three more were prepared later that year, the last of which

was again on ijtihad, and is supposed to be a revised

version of the controversial one of 1924. All six lectures

were delivered at Aligarh University in late 1929 and published

as Six Lectures on the Reconstruction of Religious Thought

in Islam from Lahore in 1930. Another lecture was later

delivered at Aristotelian Society London in 1932 and added

to the second edition, which is our definitive version of

the book and was published by Oxford University Press, UK,

in 1934 as The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in

Islam. Comparative study of the two editions has shown

that there were no fundamental changes apart from minor

rephrasing of certain sentences and addition of the seventh

lecture.[1]

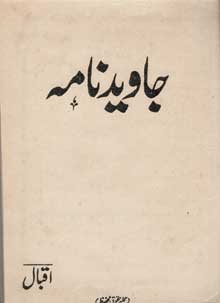

Almost a year before starting his preparation

for the first three lectures, Iqbal had started his fifth

book of poetry, Javidnama. It was going to be his

greatest work, took several years in the making and was

finally published in 1932. Hence it can be safely assumed

that throughout the preparation of his Reconstruction

lectures, Iqbal was simultaneously working on Javidnama.

Yet he was also an elected member of the Punjab provincial

legislature from 1926 to 1930 and the cumulative result

of his evolution as a practicing politician was his presidential

address at the annual session of the All-India Muslim League

in Allahabad on December 30, 1930. In the present paper

it will be called the Allahabad Address.

It is surprising that a comparative study

of these texts has never been carried out. Such a study

would have revealed a systematic coherence that exists between

these three texts but which has gone unnoticed for more

than seventy years. Strange it may seem but there is enough

linguistic evidence there to suspect that Iqbal deliberately

concealed some of these connections in a kind of “secret

code".

Discovering

linguistic coherence Discovering

linguistic coherence

| |

Reconstruction |

Javidnama |

| 1 |

Knowledge

and Religious Experience |

The Sphere

of Moon

|

| 2 |

The Philosophical

Test of the Revelations of Religious Experience |

The Sphere

of Mercury |

| 3 |

The Conception

of God and the Meaning of Prayer |

The Sphere

of Venus |

| 4 |

The Human

Ego - His Freedom and Immortality

|

The Sphere

of Mars |

| 5 |

The Spirit

of Muslim Culture |

The Sphere

of Jupiter

|

| 6 |

The Principle

of Movement in the Structure of Islam

|

The Sphere

of Saturn |

| 7 |

Is Religion

Possible?

|

Beyond the

Spheres |

In my book The Republic of Rumi: A Novel

of Reality (2007)[2]

I have tried to show internal coherence in the canon of

Iqbal’s writings in some detail. Here I shall briefly

point out three aspects of linguistic coherence between

the Reconstruction and Javidnama with

some references to the Allahabad Address. These

three aspects are:

- Similarities in structure

- Embedded allusions

- Jigsaw reading

To begin with, the Reconstruction

consists of seven lectures and Javidnama seven

chapters. How ironic, that it was never noticed that each

lecture covers the same topic which is the focus of the

corresponding chapter of Javidnama!

Readers already familiar with both books can

see the correspondence between structures from this table.

For others this correspondence will become evident from

related discussions offered in the rest of this paper.

From this similarity in the structure of both

books we may now move on to an investigation of embedded

allusions. The most obvious allusion occurs at the very

end of each book. The last lecture of the Reconstruction

ends on a passage from the prologue of Javidnama,

where Rumi is inviting Iqbal to the spiritual odyssey. Below

this passage occurs the reference, i.e. “Javid Nama,”

and hence the title of that book becomes the very last word

on which the Reconstruction culminates. On the

other hand, in the epilogue of Javidnama, ‘An

Address to Javid: A Few Words With the Posterity’

the author mentions that he has “condensed two oceans

in two cups” and expressed his ideas in two manners:

That one is in the difficult language, using

the terminology of the West,

This one is an ecstatic song from the strings of a harp.

The origin of one is contemplation, the origin of the

other is thought,

May you be the inheritor of them both!

A footnote by Iqbal himself on the first line

says: “Allusion to the book, The Reconstruction

of Religious Thought in Islam.” This “cross-referencing”

between the two books is the clearest example of embedded

allusions through which Iqbal expected his readers to undertake

a comparative study of both books and not to read them in

isolation.

Another cross-reference, less visible than

this one, occurs at the very beginning of the first lecture

of the Reconstruction, where Iqbal mentions that

certain questions are common to religion, philosophy, and

higher poetry. These three domains are represented in the

first chapter of Javidnama by three stations on the Sphere

of Moon, i.e., the cave of the metaphysician Vishvamitra,

the valley of the perennial muse Sarosh, and Yarghamid or

the Valley of Tawasin, which contains cryptic tablets of

four prophets.

Next we may consider what is described in

language teaching as “jigsaw reading.” It is

an exercise where a text is broken down into pieces and

each piece is put up on the wall in a separate corner of

the room. Students or readers are asked to reassemble the

text by reading the pieces distributed over different places

and rearranging the whole text in the correct order. Language

teachers use this activity in order to nurture the powers

of making correct inferences. Iqbal seems to have used something

similar to this technique, and the most interesting example

is a chunk in the Allahabad Address which can be

inserted into the preface of the Reconstruction

with full justification and for significant results. In

the Allahabad Address, Iqbal says, “One of

the profoundest verses in the Holy Qur’an teaches

us that the birth and rebirth of the whole of humanity is

like the birth and rebirth of a single individual.”

He doesn’t quote the verse nor gives reference but

goes on to say:

Why cannot you who, as a people, can well

claim to be the first practical exponent of this superb

conception of humanity, live and move and have your being

as a single individual?

The verse to which Iqbal is referring in the

Allahabad Address is actually quoted in the ‘Preface’

of the Reconstruction:

‘Your creation and resurrection,’

says the Qur’an, ‘are like the creation

and resurrection of a single soul.’ A living experience

of the kind of biological unity, embodied in this verse,

requires today a method physiologically less violent and

psychological.

We can see that here Iqbal has abstained from

commenting on the verse, due to which we cannot be sure

what kind of biological unity, according to him, is embodied

in it. This problem is solved if the passage is read together

with Iqbal’s commentary in the Allahabad Address.

The result, in the minds of the readers, will be the following

inference (in which the sentence from the Allahabad

Address has been italicized):

‘Your creation and resurrection,’

says the Qur’an, ‘are like the creation and

resurrection of a single soul.’ A living experience

of the kind of biological unity, embodied in this verse,

requires today a method physiologically less violent and

psychological. Why cannot you who, as a people, can

well claim to be the first practical exponent of this

superb conception of humanity, live and move and have

your being as a single individual?

It appears from this inference that the method

suggested here is in fact the realization of national unity

– in other words the formation of a Muslim state based

on this unity. It also explains the next lines of the ‘Preface’:

“In the absence of such a method the demand for a

scientific form of religious knowledge is only natural.”

Since true unity of a nation is a creative act, each individual

in a society based on such unity would be empowered to have

a living experience of the amazing “biological unity”

embodied in the verse of the Qur’an. The demand for

a scientific form of religious knowledge would be unnatural

in such a society because evidence for religious truths

will be abundant in the world within and without. However,

in the absence of such a method the demand for a scientific

form of religious knowledge is only natural.

This overview of linguistic coherence between

the three texts of Iqbal makes it obvious that the author

intended us to study these texts coherently. Now we should

consider the question: Why did he do so?

Implications

of linguistic coherence Implications

of linguistic coherence

Modern

mind likes to make inferences. What we call “jigsaw

reading” was being offered in one form or another

by such masters as Joyce, Yeats and Eliot even in the days

of Iqbal. However, what those European masters failed to

do was to harness the powers of inference in the service

of universal truth. Engagement with their literature becomes

relative, subjective and essentially dependent on individual

interpretation. Iqbal engaged the same techniques –

and a detailed analysis of his verbal art will show that

he excelled his contemporaries in doing so – but truth

never becomes relative in his art. This is his achievement

as a linguistic genius and in this he stands unparalleled

in modern literature. However, we must delve deep enough

into the canon of his writings in order to see this miracle

of verbal art. Modern

mind likes to make inferences. What we call “jigsaw

reading” was being offered in one form or another

by such masters as Joyce, Yeats and Eliot even in the days

of Iqbal. However, what those European masters failed to

do was to harness the powers of inference in the service

of universal truth. Engagement with their literature becomes

relative, subjective and essentially dependent on individual

interpretation. Iqbal engaged the same techniques –

and a detailed analysis of his verbal art will show that

he excelled his contemporaries in doing so – but truth

never becomes relative in his art. This is his achievement

as a linguistic genius and in this he stands unparalleled

in modern literature. However, we must delve deep enough

into the canon of his writings in order to see this miracle

of verbal art.

On the basis of what has been stated here,

we can formulate the following parameters for a linguistic

study of The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in

Islam:

- Its structure is organic, where one part

explains the other parts and some parts may reflect the

whole.

- It is linguistically coherent with other

writings of Iqbal, at least with Javidnama and

the Allahabad Address, and a proper study of

this book should not ignore those other texts.

- A study of this book cannot be based on

preconceived notions about the issues tackled in it because

previous knowledge from external sources may hinder the

discovery of coherence in the text itself (this is the

common shortcoming of most previous studies of this book).

On these conditions, let’s now study

some basic aspects of this book:

- What questions does it try to answer?

- What perspectives does it adopt while answering

them?

- How does it propose to reformulate our

knowledge of the world?

- In what manner does the author hope his

work to be relevant beyond his own lifetime?

The fourth question may not be asked of an

ordinary book of philosophy but we are justified in asking

it of a work of literature and verbal art. That is what

The Reconstruction is in addition to being a great work

of modern philosophy.

Seven

questions Seven

questions

The

Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam opens

with some questions which, according to Iqbal, are common

to religion, philosophy and higher poetry: The

Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam opens

with some questions which, according to Iqbal, are common

to religion, philosophy and higher poetry:

What is the character and general structure

of the universe in which we live? Is there a permanent

element in the constitution of this universe? How are

we related to it? What place do we occupy in it, and what

is the kind of conduct that befits the place we occupy?

These questions are common to religion, philosophy,

and higher poetry.

M. Suheyl Umar has very aptly pointed out

that in fact these four question marks embody six questions.[3]

I would suggest that we can add one more question: “Is

religion possible?” That is the title of the seventh

lecture and may even be reformulated according to the definition

of religion offered in it, i.e. religion in its higher form

is a direct vision of the Ultimate Reality. This gives us

a total of seven questions, which are as follows:

- What is the character of the universe

in which we live?

- What is its general structure?

- Is there a permanent element in the constitution

of this universe?

- How are we related to it?

- What place do we occupy in it?

- What is the kind of conduct that befits

the place we occupy?

- Is it possible to have a direct vision

of the Ultimate Reality?

We find that one of these questions is answered

in each lecture of The Reconstruction in the same order.

The same questions are tackled in the seven chapters of

Javidnama, again in the same order.

Philosophy,

higher poetry and religion Philosophy,

higher poetry and religion

With

the exception of the last one, these questions are common

to philosophy, higher poetry and religion. Since the Reconstruction

is a book of philosophy it obviously answers these questions

in a manner of “free inquiry” (which, according

to Iqbal, is the spirit of philosophy), yet it treats religion

“on its own terms” and keeps it as “something

focal in the process of reflective synthesis” (which,

due to the very nature of religion, are pre-requisites for

philosophical analysis of religion according to Iqbal). With

the exception of the last one, these questions are common

to philosophy, higher poetry and religion. Since the Reconstruction

is a book of philosophy it obviously answers these questions

in a manner of “free inquiry” (which, according

to Iqbal, is the spirit of philosophy), yet it treats religion

“on its own terms” and keeps it as “something

focal in the process of reflective synthesis” (which,

due to the very nature of religion, are pre-requisites for

philosophical analysis of religion according to Iqbal).

While the answers offered in the Reconstruction

have been discussed at great length in the literature

of Iqbal Studies, the questions themselves have seldom been

kept as the focal points for each lecture because the text

of the Reconstruction is not usually seen as an

organic unity. Consequently, scholars have complained that

it becomes very difficult to follow the bent of the author’s

mind at certain points. At such points it may be helpful

to refer back to the basic question that underlies all the

arguments in a particular chapter. For instance, the first

chapter is ‘Knowledge and Religious Experience’

but the underlying question which determines the position

of this lecture with regard to the general body of world

philosophy is: “What is the character of the universe

in which we live?” Hence Iqbal’s answer to this

question (in the passage that begins, “What, then,

according to the Quran, is the character of the universe

which we inhabit?”) becomes central to the whole lecture

and it should be kept in mind even for understanding the

declared subject of the lecture, i.e. ‘Knowledge and

Religious Experience’.

It is further important to remember that Iqbal

equates the universe with the Quran, and most of what is

true about the universe is to be used as a key for understanding

the Quran. In the light of this proposition, the question

about the character of the universe is also a question about

the general character of the Quran with due regard to the

essential difference between the word of God and “a

fleeting moment in the life of God” (which is how

Iqbal sees the world of Nature). According to Iqbal, the

universe is:

- not the result of a mere creative sport;

- a reality to be reckoned with;

- so constituted that it is capable of extension;

- something whose mysterious swing and impulse

is even reflected in the passing of day and night, and

which is one of the greatest signs of God;

- carries in it the promise of a complete

subjugation by the human being “whose duty is to

reflect on the signs of God, and thus discover the means

of realizing his conquest of Nature as an actual fact.”

The first two of these characteristics can

be directly applied to the Quran but the rest need explanation.

The universe can show its capability of extension materially

but the Quran as a complete and unchangeable text will show

this capability only in terms of its meaning. However, since

its text is an organic unity, even the extension of meaning

occurs organically and is therefore more real than, and

different from, a mere accumulation of commentaries. Likewise,

while the universe carries in it the promise of “a

complete subjugation by the human being,” the Quran

empowers the humanity to this end by helping it to “reflect

on the signs of God, and thus discover the means of realizing

[their] conquest of Nature as an actual fact.”

The fact that Iqbal held the Quran as a role

model even for the linguistic structure of his verbal art

gives us some important clues for understanding his poetry.

In Javidnama, the same seven questions are handled

in corresponding chapters but while the aim of philosophy

is to tell, the aim of poetry is to show. In the Reconstruction,

Iqbal was trying to tell us about a world that was not yet

born (“the day is not far off when Religion and Science

may discover hitherto unsuspected mutual harmonies,”

he said since the day had not arrived by then). In his poetry

he showed us the world about which he was telling in his

prose (“May you be the inheritor of them both!”).

The intricacies of the linguistic structure of Javidnama

reflect the five characteristics of the universe, especially

using the Quran as a role model for achieving this end through

language.

I will give only one example here from the

first chapter. This chapter ought to correspond to the first

of the seven questions: “What is the character of

the universe in which we live?” The five characteristics

of the universe described by Iqbal in the Reconstruction

find a practical demonstration here. For instance, the first

characteristic, that the universe is not the result of a

mere creative sport, is reflected in the fact that even

the ghazal of Sarosh has seven couplets, each touching upon

one of the seven basic questions. The first couplet that

should reflect on the question of the character of the universe

in which we live, is:

I fear that you are rowing your ship in

a mirage;

Born within a veil, you die within a veil.

In this manner, each couplet also provides

the preview of a subsequent chapter of Javidnama where

the same question will be taken up more exclusively. The

implications of this device are enormous. For instance,

suppose we wish to study the character of Sarosh. How should

we go about it? The poet could have told us about it but

he didn’t. Instead, he gave us her monologue on the

seven questions which we are answering for ourselves. We

judge the character of Sarosh by comparing her reflections

with our own, and by comparing them with the other realities

of her world as they unfold in Javidnama. Thus,

by chiseling down the ghazal of Sarosh to seven couplets

around the basic questions, the poet provides us an opportunity

for seeing the characteristics of Sarosh in an endlessly

greater detail than would have been possible by any number

of vivid descriptions. On one hand, the poet has virtually

created the possibility for each reader to form a different

opinion about Sarosh, while on the other he has provided

a tangible criterion against which the various interpretations

by various readers can be judged. That criterion is the

world of Javidnama, into which the poet keeps pulling

us deeper until we become the true protagonist of the story

itself. Thus the world presented in Javidnama carries

in it the promise of “a complete subjugation”

by the reader while the text of Javidnama itself empowers

us for this end by helping us to “reflect on the signs

of God, and thus discover the means of realizing [our] conquest

of Nature as an actual fact.” Indeed, the linguistic

structure of Javidnama is “not the result

of a mere creative sport.”

It is interesting to note that in the opening

paragraph of the first lecture where Iqbal differentiates

between the functions of religion, philosophy and higher

poetry, he says, “But the kind of knowledge that poetic

inspiration brings is essentially individual in its character;

it is figurative, vague, and indefinite.” Now it should

become obvious that he didn’t use these adjectives

in pejorative sense.

Having considered philosophy and poetry, we

may now move on to religion. If the answers to these questions

are found in religion then they must be there in the Quran,

and if they are to be found in the Quran then they must

also be contained in its first chapter, ‘The Opening,’

which is regarded as a summary of the whole Book. Incidentally,

the chapter consists of seven verses (which makes us wonder

whether Iqbal had it in mind when he formulated seven questions

that could cover the general history of human thought).

The seven verses of ‘The Opening’ are:

- In the name of Allah, the Mercy-giving,

the Merciful

- Praise be to Allah, Lord of the Universe,

- The Mercy-giving, the Merciful,

- Ruler of the Day of Repayment.

- You do we worship and You do we call on

for help.

- Guide us along the Straight Road,

- The road of those whom You have favored,

with whom You are not angry, nor who are lost.

The connection between the seven questions

and the seven verses of the Quran is obvious from the third

verse onwards: Is there a permanent element in the constitution

of this universe? “The Mercy-giving, the Merciful.”

How are we related to it? “Ruler of the Day

of Repayment.” And so on.

In those instances where this connection is

not so obvious, for instance, in the case of the first two

questions, some observations on the Reconstruction

help us discover the connection. For instance, the first

verse is, “In the name of Allah, the Mercy-giving,

the Merciful.” The first question is, What is the

character of the universe in which we live? In the first

lecture, Iqbal specifically answers this question by pointing

out five characteristics of the universe. If we keep them

in mind, we not only find the connection between this question

and the first verse of the Quran but we also find a very

interesting perspective on that most-oft repeated verse

of the Quran.

Five

perspectives Five

perspectives

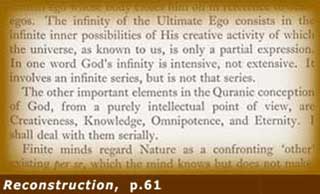

Each

of the seven questions may be undertaken at five levels,

as is evident from Iqbal’s conception of God. In the

third lecture of the Reconstruction, he points

out that according to Islamic conception, God is: Each

of the seven questions may be undertaken at five levels,

as is evident from Iqbal’s conception of God. In the

third lecture of the Reconstruction, he points

out that according to Islamic conception, God is:

- intensively infinite,

- creative,

- knowing,

- powerful, and

- eternal.

It is quite clear that Iqbal’s conception

of the character of the universe as discussed above is also

derived from his conception of God. The five elements listed

here correspond to the five characteristics of the universe

described earlier, but the correspondence occurs in the

inverse order:

- not the result of a mere creative sport;

(God is eternal)

- a reality to be reckoned with; (God

is powerful)

- so constituted that it is capable of extension;

(God is knowing)

- something whose mysterious swing and impulse

is even reflected in the passing of day and night, and

which is one of the greatest signs of God; (God is

creative)

- carries in it the promise of a complete

subjugation by the human being “whose duty is to

reflect on the signs of God, and thus discover the means

of realizing his conquest of Nature as an actual fact.”

(God is intensively infinite)

Even the seven questions, and hence the seven

lectures, are derived from these five elements by extending

the first element (God is eternal – the universe

is not the result of a mere creative sport) into three stages:

character of the universe, its general structure, and the

permanent element in it. Yet another linguistic feature

of the Reconstruction that has gone unnoticed is

that each of the first two lectures ends with an announcement

of the next, while each of the second and the third opens

with a recap of the previous one. This device turns the

first three lectures into a mini-series (the other four

lectures do not start or end with such cross-references),

and the mini-series together explains one element in the

conception of God, i.e., He is eternal – and the corresponding

characteristic of the universe, i.e., not the result of

a mere creative sport.

If we take these five elements as five perspectives,

then each question can be answered in five different ways

depending on which perspective is taken while answering.

The five perspectives correspond to five layers of reality,

which are:[4]

- Things as they are, or the Wisdom of Adam

– based on our understanding that God is eternal

- Principles, or the Wisdom of Angels –

based on our understanding that God is powerful

- Potentials, or the Wisdom of Soul –

based on our understanding that God is knowing

- Contrasts, or the Wisdom of Love –

based on our understanding that God is creative

- Resurrection, or the Wisdom of Civilization

– based on our understanding that God is intensively

Infinite

It is possible to have functional models of

knowledge without relating them to an Ultimate Reality but

in that case the functionality of each branch of knowledge

becomes restricted to its domain and any correspondence

with other branches of knowledge is mechanical and arbitrary.

Indeed that has been the case so far. However, recent trends

in human thought, especially the American thought, have

displayed an increasing desire for holistic worldviews.

Iqbal’s conception of God deserves our special attention

in this context. On one hand it is consistent with the deepest

truths of metaphysics while on the other hand it is remarkably

free of dogmatic underpinnings. Hence it facilitates a holistic

approach that connects the functions of various disciplines

in a manner that the whole becomes more than the sum of

its parts.

Functions

of knowledge Functions

of knowledge

In

the Wisdom of Adam, where we interact with things as they

are, we merely formulate questions (such as the seven basic

questions listed above). Answers at this level can be provided

through speculation (philosophy), inspiration (higher poetry)

or revelation (religion) but empirical evidence for sophisticated

answers may not be available. In

the Wisdom of Adam, where we interact with things as they

are, we merely formulate questions (such as the seven basic

questions listed above). Answers at this level can be provided

through speculation (philosophy), inspiration (higher poetry)

or revelation (religion) but empirical evidence for sophisticated

answers may not be available.

Science and ethics (and hence philosophy in

general) is concerned with principles. They are the second

layer of reality and correspond with the fact that God is

powerful. Hence science and ethics aim at empowering us

most directly – science by giving us command over

the physical world and ethics by giving us command over

the human world. In either case, this command comes through

a balance between submission and assertion: we can assert

our will over the forces of nature only by submitting to

them and over the human society only by submitting to the

values of goodness. Iqbal identifies this wisdom with angels,

who are powerful and who manipulate the hidden forces of

the universe on God’s command.

Psychology deals with potentials, which is

the third level of reality and corresponds with the fact

that God is knowing. Hence psychology aims at giving us

knowledge of ourselves, and in his seventh lecture, Iqbal

envisions a futuristic psychology that should extend our

knowledge of ourselves to an awareness of the inherent unity

between us and the rest of the universe. He identifies this

wisdom with the soul.

Art and language deal with application of

principles and hence they operate among contrasts and polarities

of all sort– beginning with the fundamental contrast

between the vast potentials of the soul and the fewer applications

possible in the world at any given time. This is the fourth

layer of reality and corresponds with the fact that God

is creative. Iqbal identifies it with love.

Religion is the only institution that is concerned

with life after death and aims at empowering the human being

to be resurrected beyond this world. It corresponds most

directly to the fact that God is intensively Infinite. Iqbal

identifies religion with civilization. The life of each

civilization is determined by the formation of fresh ideals

and creation of new values, and the birth of a civilization

is like resurrection of humanity– “Your creation

and resurrection are like the creation and resurrection

of a single soul,” the Qur’an says in a verse

that is quoted by Iqbal at significant points. Historically,

too, religion has been the originator of nations and hence

the guiding force in the evolution of human civilization.

Redefining

the historical context of the Reconstruction Redefining

the historical context of the Reconstruction

“The

day is not far off when Religion and Science may discover

hitherto unsuspected mutual harmonies,” Iqbal wrote

in his ‘Preface’ to the Reconstruction.

The day has arrived now but it is going unnoticed by the

intelligentsia of Pakistan mainly due to one crucial mistake

made by some of our best minds soon after independence.

We misunderstood the decline of the West as the decline

of humanity. This mistake deserves some elaboration due

to its crucial importance for our future existence. “The

day is not far off when Religion and Science may discover

hitherto unsuspected mutual harmonies,” Iqbal wrote

in his ‘Preface’ to the Reconstruction.

The day has arrived now but it is going unnoticed by the

intelligentsia of Pakistan mainly due to one crucial mistake

made by some of our best minds soon after independence.

We misunderstood the decline of the West as the decline

of humanity. This mistake deserves some elaboration due

to its crucial importance for our future existence.

The birth of modern times is symbolically

attributed to the year 1776. Regardless of the accuracy

of this placement, at least by the end of that century it

had become visible to the aware minds in the West as well

as the East that times have changed. The question was whether

the change should be accepted or rejected. Of course, it

depended on whether the change was temporary or permanent,

and whether the spirit of modern times was good or bad.

Hence it posed three basic questions to the thinkers of

the age:

- Are modern times passing or permanent?

- Are they good or bad?

- Should they be accepted or rejected?

While unprecedented changes were taking place

every day it was impossible to assume that any change could

be permanent. From this premise, there were eight possible

answers to the remaining two questions, out of which only

two were logically acceptable:

- Modern times are passing but good and

should be accepted

- Modern times are passing and bad, and

should be rejected

- Modern times are passing but good and

should be rejected

- Modern times are passing and bad, but

should be accepted

Obviously, the last two propositions are only

theoretically possible but they are logically absurd and

need not concern us here. Out of the first two, the proposition

that modern times are passing but good and should be accepted

was adopted by the Romantics. The second proposition, viz.

the modern times are passing and bad, and should be rejected,

was adopted by the conservatives (and would also become

the position of the Marxists still later in the century).

This was the situation in 1800.

Over the next hundred years two basic changes

took place. The first was that it was by then possible to

assume that the modern times were permanent. This assumption

would have been incomprehensible to Wordsworth, Coleridge

and Goethe but it seemed natural to Conrad, Kipling and

Eliot.

The second change was that the Western colonialism

had planted the seeds of its own demise in the East and

the mind of Europe had become aware of it. Yet it could

do nothing about it because such was the spirit of modern

times that empires could not be built on brute force alone.

They required mandates, treaties and at least pretence of

disseminating modern knowledge. Even these pretenses were

enough to empower the oppressed. The actual collapse of

the Western empire happened in the middle of the twentieth

century but the principles that led to it became evident

to the East as well as the West by the 1890’s. Obviously,

the results were different – in fact opposite –

in each case. The East adopted the position of the Romantics:

the modern times were passing but good and should be accepted

(of course, in the East they were to be accepted on Eastern

terms). The finest representation of this Eastern Romanticism

were Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and Iqbal.

In the West, on the other hand, new propositions

stemmed out of the fatalistic assumption that the modern

times were permanent. Out of the four propositions theoretically

possible from this assumption, only one is logically impossible:

- Modern times are permanent but good, and

must be accepted

- Modern times are permanent and bad, but

must be accepted

- Modern times are permanent and bad, and

must be rejected

- Modern times are permanent and good, but

must be rejected

The fourth proposition is logically impossible.

Of the rest, the first was the position of early modernists

of the 1890’s. That the modern times were good and

permanent and must be accepted was the premise hidden beneath

all the ambivalence of Nietzsche towards good and evil.[5]

This premise found a more direct expression through the

bards of Western colonialism in the later nineteenth century

but the fatalism implied in accepting any set of circumstances

as permanent is only one step away from accepting those

times as bad: good times would appear bad after a while

if you cannot alter them by choice. Hence the early modernism

developed into its later schools of deep pessimism, most

characteristically represented by T. S. Eliot. The proposition

underlying the works of these later modernists as well as

the post-modernists is that the modern times are permanent

and bad but must be accepted.

This position is suicidal in a dignified manner.

A dignified suicide was indeed how Europe looked upon its

obligation to wrap up its empire in the East. Unfortunately

certain minds in the East also borrowed this new premise

from Europe. Of course, given the fact that the East at

that time had not started receiving any dividends on the

modern times, the premise had to be modified so that it

became the third proposition listed above: modern times

are permanent and bad, but must be rejected. When you stand

up to reject something bad which cannot be changed because

it is permanent, what do you do? Archival footage of Gandhi’s

followers turning up for a voluntary beating by the police

should serve as a graphic illustration of the implications

of this proposition. It also explains Tagore’s alliance

with the modernist poets of the West, the overwhelming appreciation

of his poetry by them and the unrelenting efforts in the

West to turn Gandhi into a media celebrity, a living cult

and a role model for the Third World countries. “I

do not mystify anybody when I say that things in India are

not what they appear to be,” Iqbal stated at the end

of The Allahabad Address. “The meaning of this, however,

will dawn upon you only when you have achieved a real collective

ego to look at them.”

The outlook we adopted five years after the

birth of Pakistan was not consistent with the collective

ego achieved by the massed who created this great country.

Some of us misunderstood that the proposition of the Western

modernists that “the modern times are permanent but

bad but must be rejected” was a confession that the

West was evil. As a free nation of the East it should concern

us less whether the West is evil or not. What should concern

us more is what role can we play in the future of humanity?

This is where Iqbal comes in with the fundamental premise

of a Romantic: “the modern times are passing but good

and must be accepted.”

What does it mean to accept the modern times

when the West no longer has jurisdiction over us except

what privileges we may grant it out of our folly? This is

the question which is answered in The Reconstruction

of Religious Thought in Islam, but the question is

of such overwhelming significance that the search for answer

must entail a creative engagement with the book rather than

a mere understanding of it. That is the task that lies ahead

of us since it has never been undertaken before.

A

new basis for comparison A

new basis for comparison

The

proper comparison of Iqbal is not with the decadent stream

of golden words emerging out of Europe, especially France,

in the twentieth century, which was like the suicide attack

of European imperialism against the intellectual frontiers

of the Third World. The proper comparison of Iqbal is with

that life-giving current of thought which is practically

shaping the destiny of our world and also framing the New

World Order. The

proper comparison of Iqbal is not with the decadent stream

of golden words emerging out of Europe, especially France,

in the twentieth century, which was like the suicide attack

of European imperialism against the intellectual frontiers

of the Third World. The proper comparison of Iqbal is with

that life-giving current of thought which is practically

shaping the destiny of our world and also framing the New

World Order.

By now Iqbal has been accepted as one of the

greatest poets this world has ever produced. It means that

we must be careful in picking up comparisons for him, for

he can only be compared with the best. However, as Yeats

pointed out in 1920:

The best lack all conviction, while the

worst

Are full of passionate intensity.[6]

It would be futile to compare Iqbal with those

who lack conviction. It is true that the highest names in

thought and literature of the twentieth century fall under

this category but Yeats was wrong in calling them the best.

Nor were those who were full of passionate intensity worst

except from the peculiarly biased outlook of Yeats. They

were the bestsellers and blockbusters influencing modern

consciousness and thus shaping a new world. It is a good

world, but its goodness escaped the notice of Yeats because

the darkness dropped again too soon while he was reading

from Spiritus Mundi. Ironically, the beast described by

him in ‘The Second Coming’ had already been

envisioned by Iqbal long before him and had been described

rather differently than Yeats. The description given by

Yeats in his 1920 poem was:

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words

out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

In a ghazal titled ‘March 1907’

(and written in that month), Iqbal had said:

The lion that leapt out of the desert and

overthrew the Great Roman Empire

Will be reawakened, so have I heard from the angels.[7]

Yeats saw the image of Spiritus Mundi while

Iqbal heard about it from the angels. Yeats interpreted

it as rebirth of bloodthirsty Hellenism whereas Iqbal saw

it as the rebirth of freedom, equality and universal brotherhood

as enunciated by Islam. In either case it was linked with

the death of Western imperialism – a cause for disillusionment

to Yeats (despite his links with the Irish freedom movement)

but quite understandably a cause for jubilation to Iqbal.

“In view of the basic idea of Islam

that there can be no further revelation binding on man,

we ought to be spiritually one of the most emancipated peoples

on earth,” he says at the end of the sixth lecture

in The Reconstruction. “Early Muslims emerging out

of the spiritual slavery of pre-Islamic Asia were not in

a position to realize the true significance of this basic

idea. Let the Muslim of today appreciate his position, reconstruct

his social life in the light of ultimate principles, and

evolve, out of the hitherto partially revealed purpose of

Islam, that spiritual democracy which is the ultimate aim

of Islam.” This premonition about the future is apparently

based on the same vision of “a shape with lion body

and the head of a man” which was also seen by Yeats

but interpreted in the opposite manner:

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour comes round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

The age of European imperialism came to an

end with the Second World War. A new world has come into

being but we are living in its early phase. Since it is

a new world, it is yet to find its classics. It is not surprising

that the Nobel prizes for literature have been going mostly

to authors from countries which are not leading the world.

It is easy for these authors to adhere to the value system

of a dead world that passed away with the Second World War.

An illusion that the colonial world is still alive is given

to us through the efforts of such authors from the Third

World who follows the pessimist stance of the European masters

of the twentieth century: “the modern times are bad

but permanent” (whether the modern times should be

rejected or accepted makes little difference once you accept

this premise). Of course, these intellectuals, whether from

the East or the West, not only feed the nostalgia of Europe

but also give it a much-needed self-esteem by letting it

imagine that the world didn’t become any better after

obtaining freedom from its clutches. Self-depreciating writers

from East as well as West are duly rewarded by European

gods of art and letter for singing this swan song on a broken

harp. Hence we find that the most well-reputed names in

art and letter continue lacking in conviction.

As long as we keep looking up to this pedestal

of intellectual greatness, which is in fact a funeral-pyre,

we cannot realize that a new world has no classics of its

own and therefore its ideals are represented by bestsellers

and blockbusters that will become classics when this world

grows up. Nietzsche, Conrad, Kafka, Yeats and Eliot may

be worshipped in the lecture halls of Western madrasahs

but they are not shaping our world (and shouldn’t

we be thankful for that!).

Among these bestsellers, Iqbal is a godsend.

He is the only established authority from higher literature

who celebrated the conception of this new world before it

was born. As a thinker he is already accepted by five nations

as their ideological role model. Among the giants of such

stature he is the only one whose language belongs not only

to the Olympian heights of the best poetry and philosophy

but also to the classrooms, parliaments and cinema halls

at the same time – places where minds are being shaped

and life being directed. The significance of the Reconstruction

becomes fully evident only when it is taken out of the intellectual’s

closet and placed before the practical realities of a new

world.

Notes

and references Notes

and references

[1]

ˆˆ This has been shown by Dr.

Rafiuddin Hashmi in his pioneering study of Iqbal’s

texts, Tasanif-i-Iqbal ka Tahqiqi-wa-Tawzihi Mutalia

(Urdu) published by Iqbal Academy Pakistan, Lahore.

[2] ˆˆ

The Republic of Rumi: a Novel of Reality by Khurram

Ali Shafique (2007), published by Iqbal Academy Pakistan,

Lahore.

[3] ˆˆ

In a group discussion conducted at Iqbal Academy Pakistan

in July 2007. Available on tape but not yet printed.

[4] ˆˆ

Adam, Angels, Soul, Love and Civilization are the labels

I have discovered from Persian Psalms (Zuboor-i-Ajam)

through a system of interpretation which I have described

in my book The Republic of Rumi: a Novel of Reality.

Their attributes, i.e., things as they are, principles,

etc., are of my own coinage according to my understanding

of Iqbal.

[5] ˆˆ

It is true that he talks about the advent of yet another

change in the coming of Superman, yet the doctrine of eternal

recurrence gives a very weird kind of permanence to the

modern times: they will pass but will come again, just as

they have before. Hence the modern times are passing phenomena

only superficially but in their essence they are a permanent

element of the universe which returns in never-ending cycles.

[6] ˆˆ

All quotations from Yeats in this paper are from his poem

‘The Second Coming’, first printed in 1919 and

anthologized in Michael Roberts and the Dancers in 1920.

[7]ˆˆ

‘March 1907’ was first printed in the Urdu literary

magazine Makhzan in 1907 and later included in

The Call of the Marching Bell (Baang-i-Dara)

in 1924. Translation from Urdu is my own.

A note on dates: The paper was written

in summer 2007. It got included in 'April 2007' issue of Iqbal

Review because the issue was late and came out in early

2009. |