DAWN Images November 20, 2005

The Onscreen Love of Shirin Farhad

|

|

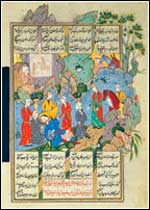

| Above

left: Miniature from Persian MSS illustrating the legend

of Shirin Farhad. Above Right: Poster of Pakistani movie

based on the legend |

The story of Shirin has been treated

in film and drama in India, Pakistan, Iran and Turkey. The best

known to us are, of course, the Indian version from the 1950s

which had songs by Talat Mehmood and, more notably, the Pakistani

version from the 1970s starring Mohammad Ali and Zeba, and featuring

music by Khwaja Khurshid Anwer (including the famous song Ishq

mera dewana by Mehdi Hasan).

Most of these dramatic versions simply followed whatever formula

happened to be current in the media at that time. The literary

refinement of the classics was seldom reflected.

Shirin was a Christian princess from Armenia and lived in the

sixth century AD. She got married to Khusrau Pervaiz, the powerful

Persian emperor of the Sassanid dynasty (and incidentally a

grandson of Nausherwan the Just). The Persians remembered her

by the name Shirin. Apparently it was a corruption of Irene

but at the same time meant ‘sweet’ in the language

of Persia.

In all probability, her marriage was a political one. Historical

facts are scarce, since the Arabs overran the country soon after

her husband’s death. Persia was reduced to a mere province

of the vast Arab empire that stretched from Spain to Sindh.

The new empire was centralist in nature, in which native cultures

were at best viewed with suspicion and at worst completely suppressed.

Pehlavi (the language spoken in ancient Persia) became a dead

language or at least it was never written again. The situation

lasted for three centuries.

Sometime in the 10th century,

the Arab empire started falling apart. Sindh, Egypt, Turkey,

Afghanistan and parts of Persia became independent, very often

under native rulers whose ancestors had converted to Islam.

Mahmud Ghaznavi, Salahuddin Ayubi and Alp Arsalan Saljuqi are

some of the best examples of these rulers.

Many of them paid nominal allegiance to the Arab caliph at Baghdad

but encouraged movements for the revival of regional biases,

cultures, and even regional jealousies. Pehlavi language could

not be revived but the pride of the Persian people (now mostly

Muslim) worked up the birth of a new language out of the old

tongue. It was the language today known as Persian — a

hybrid of Pehlavi and Arabic vocabulary, following Pehlavi grammar

in most instances but written in the Arabic script.

Mahmud Ghaznavi was among the greatest patrons of this new language

and encouraged historians to discover and record the pre-Islamic

glory of Persia. Mahmud was a staunch liberal where it didn’t

concern his prejudice against the minority sects of Islam or

his political rivalry with the Indian rulers. He also commissioned

the writing of the first great masterpiece in Persian. This

was the Shahnamah, or the Book of Kings, written by Firdausi

around 1226 AD. From this book originates the love story of

Shirin as higher literature.

Firdausi described Khusrau as a prince who fell in love with

the Armenian princess and won her hand after much effort. As

husband and wife, or king and queen, they lived like role models

of a passionate couple — sort of an earlier day Jahangir

and Nurjehan. When Khusrau’s son from another wife killed

him and wanted to marry Shirin, she asked permission to spend

a night at her dead husband’s tomb before taking a new

one. This was granted but, unsuspected, she smuggled a dagger

and stabbed herself to death over her lover’s coffin.

It is obvious that Firdausi was working from some written histories

(now lost to us) and a lot of oral tradition, but above all,

he also took into account the various folk tales that had developed

around the Persian kings by that time. These were produced by

three centuries of nostalgia about a forbidden past. In these

tales, Shirin was exceedingly beautiful and Khusrau was a passionate

young man. Apparently, the Persians had remembered him in a

very different manner than the Arab historians for whom he was

mainly the impudent monarch who failed to honour the message

of Islam in his court. However, it seems that either Firdausi

or one of the writers of these folk stories was also inspired

from a very unexpected fictional source — the Greek story

of Pyramus and Thisbe.

In that story, which was also narrated by the Latin poet Ovid

in Metamorphosis, Thisbe stabs herself at the tomb of her dead

lover Pyramus (the story later inspired that string of novels

about Romeo and Juliet that were finally adapted by William

Shakespeare for the Elizabethan stage). Apparently, Shirin became

Thisbe in the folk memory of Persia and the great poets, starting

from Firdausi, carved that image on words that will last longer

than marble and gilded stones.

Firdausi didn’t mention Farhad. However, a folk story

had developed around a sculptor, Farhad, who engineered a stream

of milk for her and then fell in love while Khusrau was still

wooing her. Khusrau invited Farhad to his court, questioned

him and then promised to give him Shirin if he removed the Bestoun

Mountain from its place as it was blocking a passage to the

royal palace.

The sculptor, in a frenzy of passion, actually removed the mountain

with his pickaxe, at which Khusrau sent an old woman to misinform

Farhad that Shirin was dead. Upon hearing this news, the sculptor

killed himself with his pickaxe.

The first great poet to weave the Farhad legend into the love

story of Shirin and Khusrau was Nizami Ganjavi, who lived in

Azarbaijan in the 12th century AD. His native city — Ganjeh

— was near Baku and hence not very far away from Armenia,

the original country of Shirin (Irene). Also, his wife Afaq,

whom he loved passionately, was a former slave girl given to

him by a king as a reward for writing a magnificent epic.

Nizami could relate himself to Farhad, only a lot more fortunate

one, for he too had worked hard (in writing an epic instead

of carving a mountain) and found a beautiful woman in reward

(which Farhad had only been promised but never actually received).

Afaq, then, was a role model of Shirin for him.

Consequently his next epic turned out to be Khusrau Shirin,

written in 1191. It was the first full-length treatment of the

story that had merely filled a chapter in Firdausi’s epic.

It was also the poem that gave birth to literally all the conventions

followed in the love poetry of Persian (and later Urdu) ever

since.

Nizami, however, depicted Shirin as in love with Khusrau. She

didn’t reciprocate to Farhad’s essentially one-sided

crush on her although she was sympathetic towards the great

sculptor. To be in love with a pauper but marry a king would

render her unfaithful and greedy, and that Nizami couldn’t

do since his ulterior motive, most probably, was to immortalize

his wife Afaq through a Shirin modelled after her.

Nizami effectively used the fate of Farhad as a mirror to Shirin

— both kill themselves with a sharp weapon but Farhad

succumbs to deceit while Shirin manages to follow her lover

in the other world. Farhad’s love did not carry the ‘grace’

(in a mystical sense), while hers did. One can almost feel that

both Farhad and Khusrau represent Nizami. The sculptor represents

the poet’s present station, which he yearns to surpass.

The king represents the station he is yearning to achieve (and

which he probably achieved as we can see in his next great epic,

Layla Majnun).

Nizami’s epic immortalized Shirin for once and for all.

There were numerous imitations of Nizami, countless renderings

of the Shirin-Khusrau tale in the centuries to come. Perhaps

the most illustrious of such imitators was the great musician

and poet Amir Khusrau, who lived in India nearly a century after

Nizami. He wrote five epic poems to match the set of five written

by Nizami, and this included Shirin Khusrau.

In this later version, however, the Persian king became a villain

(a Turk by origin and an Indian by location, Amir Khusrau could

experience little natural sympathy with the Persian king with

whom he shared nothing but a common name). Here, Shirin was

also in love with Farhad but Khusrau gained her through deceit.

Shirin was a woman who, of course loved a sculptor but married

a king out of necessity.

Other poets interpreted it as her frailty and a moral taint

in her character. (The growth of this character parallells the

growth of Cressida in European literature, who was simply an

abducted girl in Homer but gradually became a woman who leads

on two men and betrays the truer of them — ending up almost

as a harlot in Shakespeare’s play Troilus and Cressida).

The classical Urdu poets were often condescending or critical

towards Farhad. For instance, Ghalib described him as someone

who reduced the grandeur of love to free labour for the beautification

of the royal palace. In another couplet, he pejoratively stated,

“Do we not possess a liver that we should use our craft

on a mountain instead?”

Iqbal, following in the footsteps of Ghalib, mentioned Farhad

in a similar vein in his early poetry. However, in his later

poetry he became the first great Urdu poet to hail the sculptor

as a prominent symbol of struggle — sometime representing

the labour class taking a stand for their rights against the

oppressors and at other times a true craftsman who doesn’t

shrink at the Herculean dimensions of an impossible task.

With or without those refinements, and with or without the fidelity

of Khusrau, Shirin has managed to survive through the centuries,

above all through the courtesy of the poet Nizami. Her name

carries magic even today.

However, one wonders how much of this magic was her own and

how much of it belonged to Afaq, the woman who served as a muse

to the poet Nizami. Or is that the way things work in collective

memory, one image overlapping the other until the result is

a representation of what each of them brought to the icon, as

well as what the present reader is bringing to it. History is

always in the making.