On April 21, 1938, Iqbal died in Lahore. People swarmed to his house; they included Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs. His friends selected a vacant spot on the left side of the steps of the gigantic Mughal mosque as his burial place. The site belonged to the archaeological authorities and hence the Chief Minister of Punjab Sir Sikander Hayat Khan had to be contacted in the middle of his Calcutta visit. He refused (and later got himself buried on the other side of the same entrance). The British Governor was more helpful and through him the permission was secured from Delhi by the afternoon. By that time, newspapers had printed special supplements so that when the funeral procession started in the evening it contained no less than twenty thousand people. Children from the orphanage of Anjuman Himayat-i-Islam paid their homage by holding little black flags in their hands and standing silently in a queue on a nearby road. They lowered their flags when the procession passed by. It was not forgotten that the poet had started out as a fundraiser for homeless children thirty-eight years ago. The body was lowered into the grave at 9:45 pm after the funeral prayer had been offered twice – once in the playgrounds of the Islamia College (where, we are told, some fifty thousand people attended it) and a second time in the grand Mughal mosque where he had seldom missed the biannual Eid prayers in his life. His last book, an imaginary travelogue to Madinah in Persian verse was still unpublished. It came out later that year by the title he had given to it, Armughan-i-Hijaz, or The Gift of Hijaz. His last Urdu anthology was appended to it as an additional section. In March 1940, less than two years after Iqbal’s death, the All India Muslim League held its annual session in Lahore – at Minto Park, just outside the Mughal complex in which he was buried. A resolution was passed to create a Muslim state in the Northwestern provinces of India and two years after that Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the Quaid-i-Azam, published a bunch of letters written to him by Iqbal in his last days. Referring to the recent expansion of his party’s influence to the Muslim majority provinces of the sub-continent, he paid tribute to Iqbal, who had “played a very conspicuous part, though at that time not revealed to public, in bringing about this consummation.” The nationalists read this statement with suspicion. They claimed that Iqbal had only forwarded a proposal for rearrangement of provinces while he would have never approved of partitioning the country since he too had been a nationalist once. Jinnah succeeded, however, and Pakistan was carved out of India when the British gave independence to the country on August 15, 1947. Since the astrologers in India regarded the day as inauspicious, the Prime Minister designate Jawaharlal Nehru called the first session of his parliament on the 14th and let it linger on till midnight when he could greet the awakening of his country with a moving speech. The session did not adjourn until Suchitra Kirplani, who would later become the first woman Chief Minister in an Indian province, had sung Iqbal’s Saray jahan say achha Hindustan hamara (Our India is better than the whole world) alongwith Jana mana gana of the Bengali poet Tagore. The next morning in Karachi, Jinnah hoisted a green and white flag to start the first day’s work in the state that was officially seen as the brainchild of Iqbal. Here, each successive ruler would feel obliged in one way or another to pledge commitment to the “message of Iqbal.” The two states fought three wars against each other in less than three decades but Iqbal remained dear to them both. Twenty-six years later his birth centenary was celebrated in India while the Prime Minister was Nehru’s daughter – an apocryphal story went around to the effect that her late father had enjoined upon her to always honor the memory of Iqbal, who had immortalized him by mentioning him in his greatest work, Javid Nama. She initiated a second round of accolades for Iqbal by way of an international conference in New Delhi when Pakistan announced its own centennial of the poet four years later. However, it would be wrong to guess that such appreciation in India was restricted to the Nehru family – Morarji Desai, who wrested power from Indira Gandhi in the meanwhile, took pains to ensure that the conference in New Delhi takes place as planned.

Indian nationalism and Pakistan’s two-nation theory were not the only schools of thought disputing to claim him as their own. The ‘progressive’ writers of South Asia, generally having a Marxist orientation, had formed an association in 1936 and even their condolence essays on the poet’s death affirmed their literary descent from him. In some later writings Faiz Ahmad Faiz stated that Iqbal represented the new middle class against the decadent aristocratic tastes in Urdu literature. This class had emerged as a result of exposure to modern education offered by the British, said Faiz, but it was surprising that no other poet presented the experience of knowledge in his poetry. “The poetry of ideas reached perfection through Iqbal in our own times,” he wrote a year after Iqbal’s death. “The task required a great personality.” He used the case to prove that poetry of ideas could be spontaneous too. In the earlier writings the progressives had denounced Iqbal – for instance, the seminal essay by their thinktank Akhtar Husain Raipuri in 1935 accused him of being a fascist. Their change of heart came from a realization that without him, the progressive thought in Urdu poetry might not have been possible. Their own contribution to the understanding of his works was to create a widespread confusion about whether he was a socialist or not. Yet another type of opinion was represented by those who felt envy, resentment or aversion. He was not a poet and could hardly write a line without making errors, was a common slogan of the school that had its origins in the pangs of jealousy felt by contemporary poets when at the age of twenty and something he attained more renown than any other Urdu poet had acquired at a similar age. In the beginning he attempted to refute such objections with philological arguments and precedents from authentic texts but soon gave it up with a sarcastic indifference: he was a messenger and didn’t wish to be known as a poet, he said. Like all other celebrities, he too was a popular subject for gossip. In his own lifetime he was sometimes enigmatic and therefore always under the risk of being misrepresented, as he himself complained even in his earliest poems. Later, his fame gave rise to a wholesale industry of synthetic fables about his life, especially private life, until there were people claiming to have been his neighbors in cities he had never visited. Consequently there emerged a group of scholars who, perhaps finding the area of serious discussion saturated, turned their attention to a ‘psychological study’ of his mind – of course excluding his thought, which could have been too tough for these popstars of the academic world. The letters of Iqbal to Atiya Faizi (written in 1909-11 but published in 1947) were a godsend, and soon there were half-baked psychological studies of Iqbal. On closer analysis they were neither psychological nor succeeded in studying anything. The shortcomings of such writings gave birth to the complaint that Iqbal’s life was whitewashed and the true picture could emerge only if there were more details. Supply follows demand, and rumors came forward to fill the gaps. Last, but not least, was a group of hardworking and sincerely devoted but artistically challenged scholars who suffered from an irredeemable overdose of Western philosophy and an unctrollable urge to display their familiarity with difficult subjects. ‘Iqbal and Bergson,’ ‘Iqbal and post-Kantian voluntarism,’ ‘Iqbal and Schaunpenhaur,’ and every other possible conglameration of this sort became the vogue and produced copious volumes of unreadable essays, papers and books. On the shelves of Iqbaliyat in public libraries, colleges and universities these lethally boring products pushed aside the slim and slender volumes of Iqbal’s own cheerful and alive prose, which was now regarded incapable of explaining his thought. Readable efforts at critical appreciation of his works (of which there were many) came to be seen as less prestigious.

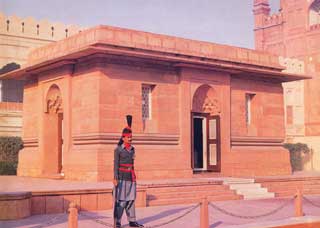

Meanwhile, Iqbal’s friends had been busy erecting a suitable mausoleum over his earthly remains. One design was rejected because it had a Catholic ethos. Another design, submitted by an architect from Hyderabad (Deccan) was found more suitable but rather too delicate. Its architect Zain Yar Jang was called to Lahore where Iqbal’s trustee Chaudhry Muhammad Husain took him to the poet’s grave. “Look, Nawab Sahib!” He said, “On one side is the moseque, which represents the religious glory of the Muslims; on the other is the fort, which represents their worldly power. The tomb between them would look nice only if it effuses simplicity with strength. Besides, these were also the prominent aspects of Iqbal’s own temperament.” Construction started towards the end of 1946 according to Zain Jang’s second design and was completed in 1950. Funds came from devotees without necessitating a general appeal to the public. The Government of Afghanistan donated lapis lazuli for the platform, sarcophagus and tombstone – Zahir Shah was the king at that time and Iqbal had raised funds to support the struggle of the Shah’s liberal father to gain the throne, visited Afghanistan on his request and mentioned him in his poems. That same year the provincial government of Punjab in the newly created Pakistan also established an Iqbal Academy in Lahore. The name was changed to Bazm-i-Iqbal when an act of Parliament created another Iqbal Academy under the federal government in Karachi in 1953 (which has since then also moved to Lahore and currently functions under the Ministry of Culture and Sports). One of the first initiatives of Bazm-i-Iqbal was to commission a standard biography from a renowned journalist, Abdul Majeed Salik, who had personally known the subject. Zikr-i-Iqbal was published in 1955. Among those who vehementaly criticized it were Agha Shorish Kashmiri, another journalist, who did the right thing for the wrong reason. Representing the morbid conscience of the masses, he complained, not that the book was superficially written as it was, but that it did not present Iqbal as a perfect role model for the youth of the nation; he should have been presented as a flawless human being. With a few exceptions owing to individuals who ran these organizations at different times, both Bazm-i-Iqbal and Iqbal Academy commendably resisted to act as censors and remained busy with organizing and disseminating knowledge on Iqbal’s life and thought. The world of Iqbal scholarship will be endlessly indebted to the efforts of these institutions as well as numerous private publishers, authors and amateurs, who laboriously preserved invaluable primary data that would have been otherwise lost with time. Morbid censors have existed in the society, however, and mainly known by three names: textbooks, newspapers and television. Each of these (with the recent exception of some private channels on television) have usually been guided by trends that reduced the discourse on Iqbal to a handful of harmless and meaningless clichés. The man who was known for an exuberant sense of humor in his own lifetime is often presented on these mediums as one who might never have said or done anything of the slightest human interest. Showing reverence to this incongruous effigy and quoting him as your favorite poet, philosopher and guide is a national duty, these sources tell the unsuspecting masses – innocent children included. The process of recognition beyond his own region, which started in his lifetime, did not diminish after his death. In England and Germany there are university chairs in his name and scholarship on him exists in many more countries, including the US, the Soviet Union and many countries in Africa and Asia. Within the Muslim World his position as the last flowering of the Persian wisdom poetry, and an important thinker of the modern times, is pre-eminent. Divergent opinions, however, are present – accused by some mystics for criticizing Hafiz, and by some staunch radicals for being too mystical, Iqbal seems prophetically true to his early verses: “Some think that Iqbal is a Sufi, while others accuse him of running after lovely dames. I am right there before everyone and yet opinions differ so much about me – what would happen if perchance I were to disappear.”

India celebrated the Iqbal Centenary in 1973 and Pakistan in 1977 (owing to disagreement over his date of birth). In retrospect the two centenaries seem to be the closing of curtains on the first phase of scholarship in the field, which remained dominated by his peers and younger contemporaries. They were too close to his own times and, more significantly, they had witnessed the unfolding of his ideas so gradually that they were set against elemental difficulties in taking a bird’s eyeview of his life and thought. Their contributions were crucial – without them the existing bank of primary sources would not have been as large. However, reorganization and reassessment was needed. A new age of Iqbal scholarship dawned and its harbinger was, not coincidentally, Javid Iqbal. He was the younger son whose name had been used as a metaphor of the future generations. From 1979 to 1984 he published the first authoritative biography of his father in three volumes, Zindah Rud. “I was only thirteen and a half at the time of Iqbal’s death,” he wrote in the foreword of the first volume. “Therefore I cannot claim to be his contemporary but my distance from his times makes it easier for me to keep an objective approach.” With the same intellectual humility that was a prominent feature of his father he stated that he was writing this book for those who would come after him because they might be able to understand his father better than him; “after all, Iqbal is a poet of tomorrow and of the future.” Merely a couple of years after the publication of the last volume of Zindah Rud came the first variorum edition of Iqbal’s poetry – although restricted to the early period. Incidentally, it was compiled by a Hindu scholar from India. The next important resource book also came from the same side of the border; it was a complete collection of letters arranged in chronological order. The landmark works of the new age of Iqbal scholarship have made it possible for the present cohort to take a holistic view of him. The older stylistics, where a favorite line was arbitrarily picked up and subjectively expanded or a fleeting emotion taken as guideline for an entire thesis is now giving way to a newer set of more detached but also more balanced writings on the life and works of Iqbal. Filtered and refracted through these layers of meaning, emotion, and contradictory opinions – “a thing inseparable from him alive or dead” – the voice of Iqbal has come down to us. |

|||||||||||||

Special

thanks to

Special

thanks to

A

Word from the Author

A

Word from the Author