|

Search the Republic of Rumi

|

|

|

|

Chapter

2

The Dark Night of the Soul

(1905-1913)

|

Early impressions

of the West

“It is my belief that a people who value

their own freedom cannot be envious of others’ liberty and

I find much evidence of this in what I see of the British society

here,” Iqbal wrote to the editor of a nationalist newspaper

of Lucknow a few months after his arrival in England. He was commenting

on the Sawdeshi movement (the movement for economic self-reliance

started by the extremist Hindus in the sub-continent). “However,

we must develop competence [to govern ourselves], and that can

come mainly from the focusing of economic norms, to which our

people have fortunately started paying attention now.” Iqbal’s

belief in the fairness of the Europeans was about to receive a

harsh reality check very soon but his fundamental approach of

seeing everything in its larger picture would remain forever.

What did Europe mean to Iqbal at age 28, when he

first set foot on its soil? It was a treasure trove of knowledge,

the seat of universal law and the house of the empire builders.

Iqbal, the genius who thought he was a know all, was adamant at

discovering Europe in all these dimensions. The vast collections

of ancient and modern writings, including rare manuscripts of

classical Muslim thought, would be unearthed by him from the libraries

and museums of England in order to reconstruct a coherent history

of metaphysical thought in Persia – a subject nobody had

written about. Secondly, he was going to study the source of the

European power, its universally applicable law, and celebrate

his mastery of it with a Bar at Law from the prestigious Lincoln’s

Inn (hopefully paving the path of material prosperity, as he must

have assumed at that time). However, all law is useless unless

there is a competent authority to execute it, and the execution

of the British law over an empire where the sun never set –

and the political supremacy of the European civilization over

all others at that time – pointed at the deeper secrets

of successful politics; the secret of empire-building, which was

once known to the Muslims but could now only be learnt from the

West. Ironically he was soon going to discard all three –

knowledge, existing law and prevalent ideas about politics. It

was his destiny to become the founder a new worldview.

The crucial turning point was a year and a half

after his arrival. ‘March 1907’ is a date he didn’t

want to be overlooked by any future biographer of his mind; he

wrote the date at the top of a ghazal that didn’t need any

heading, and he counted back his intellectual reincarnation to

this year in numerous letters, speeches and statements. Curiously

enough (but very typically) he doesn’t tell us anything

else about it. What happened, exactly, in that month? He didn’t

tell us, but obviously he wanted us to find out. Let’s not

assume, please, that it was some beautiful woman he met –

he hadn’t seen Atiya Fyzee till a month later, and Emma

Wegenast didn’t occur to him until the summer. Call him

a chauvinist if you will, but he was just not the type whom a

woman could cause to change the course of life (much less the

direction of mind, which may have been more precious to him than

life). A careful study of his life and works makes it plausible

that the big thing about March 1907 was his discovery of an answer

to the question he had raised a few years ago; in his Political

Economy, he had wondered whether poverty and needfulness could

be made extinct; he had also suggested that the answer lied in

the moral capabilities of the human race. Now he discovered a

formula for enhancing those moral capabilities: understanding

Islam not as an irrational insistence on preserving the past but

as a means for a giant leap into the future. How he arrived at

this awareness is an interesting odyssey of the mind.

“We admit the superiority of the Hindu in

point of philosophical acumen,” he had written in the introduction

to his thesis on al-Jili seven years ago. “The post-Islamic

history of the Arabs is a long series of glorious military exploits,

which compelled them to adopt a mode of life leaving but little

time for gentler conquests in the great field of science and philosophy.

They did not, and could not, produce men like Kapila and Sankaracharya,

but they zealously rebuilt the smoldering edifice of Science,

and even attempted to add fresh stories to it.” This inferiority

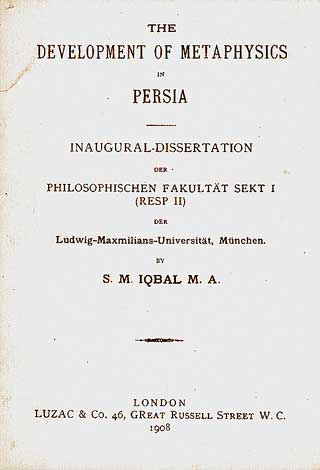

complex does not resurface anywhere in his thesis The Development

of Metaphysics in Persia (completed in February 1907 and submitted

to the Trinity College on March 7). Eighteen months of first-hand

interaction with the works of great Muslim philosophers and scientists

made him aware that the Muslims, too, had been great thinkers.

Since then the contribution of the Muslim scientists to the modern

science has not only been acknowledged but in the Muslim world

it is sometimes even overrated in ways that have rubbed out the

freshness of those great geniuses of the past, and therefore it

is difficult for us to understand Iqbal’s sense of discovery

when he first found proof of what Justice Ameer Ali in the second

volume of his Spirit of Islam, and Shibli Nomani in some of his

papers had merely suggested. Neither of these two great historians

had the kind of first-hand acquaintance with Western philosophy

which Iqbal got to have, and hence it was left for him to grasp

the full significance of the classical Muslim thought. He had

now discovered that the Muslim thinkers had not rebuilt an already

existing body of science and philosophy; they had constructed

a new, grand and magnificent edifice of thought. The ancient Greek

ideas, devoid of empirical spirit as they were, could not have

provided a basis for the modern European civilization without

input from the great Muslim mind. Islam is inherently opposed

to a duality between matter and spirit – or at least that

is how Iqbal understood it – and therefore the Muslim thinkers

had been able to unleash the hitherto unknown capabilities of

human thought. This proposition about the magnitude of human thought

contains, as we can see, its own antithesis within it. If the

human mind can only realize its true potential by engaging with

the divine revelation then thought must also be transcended in

order to collect the fruits of thought. The mystic in Iqbal told

him that this was indeed the case.

Iqbal’s renewed confidence in the intellectual

gifts of the Islamic revelation must have also led him to believe

that a system of law better than the modern one was possible –

indeed that reconstruction became his central focus towards the

later part of his life. His study of the British law even in those

days must have been moderated by a strong bias towards the superiority

of an Islamic law – not the law that existed in the antiquated

books of jurisprudence tampered by whimsical monarchs of the medieval

times, but the undiscovered law whose seeds were contained in

the Quran (later, on more than one occasion, he would suggest

that the true potential of Islam has not yet unfolded). This undiscovered

law of Islam was one of the many alternate worlds that the Holy

Book could offer and the idea was outright thrilling (the concept

of an alternate world – any alternate world – could

stir deepest emotions in Iqbal at any given moment in his life).

Last, but not least, was the challenge of the Western

political superiority. That was comparatively easy to handle,

since even in his al-Jili days, he had been proud of the military

conquests of the medieval Muslims. Now, however, he recognized

the fragility inherent in the strength of the Western civilization

itself: it had disregarded the spiritual in its eagerness to overcome

the material aspects of existence. “O dwellers of the West!

The city of God is not a marketplace,” he poured out his

feelings in the ghazal titled ‘March 1907’. “What

you have been holding as currency will now turn out to be counterfeit.”

In the same vein he goes on to say that the lion that once emerged

from the desert and devoured the great Roman Empire, is, according

to what the poet has just heard from the angels, about to reawaken.

This critique of the Western civilization and protest

against exploitation of the weaker nations may appear to be an

about turn on his earlier statement of a year ago. However, his

belief that “a people who value their own freedom cannot

be envious of others’ liberty” remained unshaken.

What changed was his opinion of the British society in general,

but the change occurred on the basis of the same principle. Such

paradigm shift often coincides with release of immense emotional

energies and an ecstatic experience of feeling liberated. For

someone born in Sialkot in the heyday of the Raj, this also meant

a recovery of political pride in ways that would have been incomprehensible

even to the British masters. It was Iqbal’s discovery of

himself, and not an encounter with some other person, that marked

the significance of March 1907 and started the process of his

psychological reconstruction.

Cambridge, Heidelberg and

Munich

|

|

| |

Iqbal’s academic pursuits in Europe and the

influence of Western philosophers on him are generally seen as

interlinked, but they need not be. Iqbal’s field of research

at Cambridge didn’t include Western philosophy, except by

way of comparison. His Ph.D. from Germany (awarded on the same

dissertation), wasn’t even issued in the area of philosophy

(although he applied for that), and technically, it was a Ph.D.

in Arabic. Iqbal’s acquaintance with the Western philosophers

– apart from what he learnt about them during early studies

in Lahore, or later teaching responsibilities there – was

mostly extra-curricular, and we cannot date his readings very

accurately. His supervisor, Dr. McTeggart, however was an expert

on Kant and Hegel, and Iqbal attended his lectures on these two

philosophers – afterwards outgrowing Kant and discarding

Hegel. It would be erroneous to state that the boundaries of Iqbal’s

metaphysics were predetermined by Kant; to put it rather frankly,

some Iqbal scholars have made too much of such superficial similarities

in order to showcase their own familiarity with hardcore philosophy.

Kant’s argument against the logical proofs of the existence

of God were useful (and Iqbal made good use of them), but Iqbal

also maintained an almost patronizing attitude towards the critic

of pure reason who had failed to recognize that thought itself

was part of the reality it tried to understand and contain; the

fundamental difference between Kant and Iqbal was that according

to Kant, the existence of God could not be proved but we should

act as if He existed; to Iqbal, a “philosophical test of

religious experience” was possible.

About the champion of antithesis, Iqbal later wrote

that “Hegel’s indifference to personal immortality

has more or less affected all those who received inspiration from

him,” and certainly Iqbal doesn’t seem to be among

them – his long-winded comparison of Hegelianism with Akbar

Allahabadi should not be interpreted as a deference to the German

philosopher; Iqbal’s love for variety could burst out in

magnanimous appreciation of ideas diametrically opposed to his

own beliefs, and his frequent appraisals of the Ahmedi movement

until the 1930’s is one case in point. Despite some initial

praise for Hegel he eventually criticized him without mercy in

The Message of the East and elsewhere, even to the extent of saying

that his system of philosophy was an empty oyster.

There was, however, one major conviction he upheld

in the later years that sounded rather like a Muslim’s compromise

with the Hegelian “indifference to personal immortality.”

Iqbal asserted (at least as early as in 1910), that personal immortality

could not be taken for granted; the human being is merely a candidate

for it. In other words, the human soul may or may not be resurrected

after death, depending on the strength or weakness of the ego.

Again, it might be observed that Shiekh Ahmad Sirhindi (Mujaddid

Alf Sani) had also spoken about the possibility of the annihilation

of some souls, although in a somewhat different context.

This was fundamentally different from the views

of McTeggart himself. Iqbal’s atheist supervisor believed

in the absolute immortality of the individual ego, held the time

and space as unreal and was rather confused between the predominance

of action and love. Iqbal’s emotional attachment to him

could be gauged from the fact that he tore up the manuscript of

a thesis on the reality of time when McTeggart criticized it bitterly.

According to Iqbal, pure time was different from serial time;

our appreciative self exists in pure time although our efficient

self exists in serial time. Of course, McTeggart apologized profusely

when a little later the same ideas received acclaim in England

through the French contemporary Bergson.

Iqbal’s advances towards the Western philosophy

were much like the metamorphosis of a lover who is at first stricken

by the majesty of a lovely face but quickly moves on after getting

fed up with the soul behind it (exactly the kind of sexual chemistry

he confesses in ‘The Inconstant Lover.’) The fountainhead

of his creative thought was neither in the East, nor in the West,

but lied in the inexhaustible riches of his own ego.

Atiya Fyzee

The encounter that has long captivated the

imagination of some biographers (and misled quite a few of them)

did take place – on April 1, 1907 in London. Atiya Fyzee’s

account of her first meeting with Iqbal offers some traces of

harmless social flirtation that faded away very quickly and gave

way to a long lasting sober friendship.

“Miss Beck [hostess of the party where

this meeting took place] had impressed on me the fact before he

arrived that he had particularly wanted to see me and being straightforward

and outspoken, I asked him the reason why,” Ms. Fyzee writes

in her book Iqbal, first published nine years after the poet’s

death. “His deep-set eyes did not reveal if he meant to

be sarcastic or complimentary when he said, ‘You have become

very famous in India and London through your travel diary, and

for this reason I was anxious to meet you.’ I told, ‘I

am not prepared to believe that you took the trouble to come all

the way from Cambridge just to pay me this compliment, but apart

from this jest, what is the real idea behind this object?’

He was a bit taken by surprise at my sudden bluntness, and said,

‘I have come to invite you to Cambridge on behalf of Mr.

& Mrs. Syed Ali Bilgrami as their guest, and my mission is

to bring your acceptances without fail. If you refuse you will

bring the stigma of failure on me, which I have never accepted,

and if you accept the invitation, you will be honoring the hosts.’”

Iqbal’s request was granted, and Ms. Fyzee

accompanied him to Cambridge a dinner and a tea party later –

the dinner was the one where Atiya’s appreciation of the

thoughtful and delicate arrangement was met with the statement

that has now become well-known about Iqbal, “I am two personalities

in one; the outer is practical and business-like and the inner

is the dreamer, philosopher, and mystic.”

The dinner was not, however, a very private one,

since some other guests had also been invited, whom Iqbal introduced

to Ms. Fyzee as “German scholars.” For all we know,

they could have been white men with bad pronunciations, since

Iqbal was known to pull pranks and in all likelihood he played

at least some practical jokes on Atiya too: her account of Iqbal’s

academic activities as well as her autobiographical ramblings

are wrought with such inaccuracies that require deliberately wrong

statements on his part or a remarkably bad memory on hers.

In all likelihood Atiya might have been the friend

anonymously mentioned by Sheikh Abdul Qadir in the preface of

The Call of the Marching Bell as asking Iqbal to write something

in Persian. He did send a few ghazals to Atiya the very next day

after her trip to Cambridge, but she or any other friend from

Cambridge could not have been the reason why he turned to Persian

for later masterpieces – he had written in Persian before,

and for all we know he didn’t write anything in Persian

for four years after the poems sent to Atiya on this occasion.

Of one thing we can be sure. If dissatisfaction

with his first marriage had sent Iqbal looking around for a second

wife, or if Atiya was contemplating settling down at that point

in life, they were far from being the perfect match for each other

and they both knew it. Iqbal, despite his brilliant sense of humor,

was also capable of giving jitters to Atiya by his mere presence.

“He was much fond of himself as a man primarily –

and a great scholar after. There was no getting out of it,”

Atiya wrote in an article published only after her death in 1967.

“My first impression of ‘Iqbal’ was that he

was a ‘complex,’ – a mixture of good and evil,

extremely self-contained and fond of his own opinion – a

bad sign, I said to myself!” Elsewhere, she assessed him

as a male chauvinist who regarded women as some sort of necessary

evil. To him, on the other hand, the emancipated woman from Bombay

must have appeared as rather too bold. If Iqbal’s first

marriage had floundered because of the high spirits of his wife

and her superior social status then any likelihood of marrying

this other woman of much higher spirits and properly aristocratic

background should have irked him just as much as his fondness

for ‘his own opinion’ was putting her off. In due

time they became good friends who understood each other very well.

EmMa Wegenast

Emma Wegenast was a different case. “German

women are incomparably fonder of domestic bonding than their English

counterparts,” Iqbal later rambled in his evening gatherings,

and Emma was indeed a German woman.

Iqbal met her during his brief stay at Heidelberg

in the summer of 1907. She was some kind of a language coach (and

not a university teacher as naively believed by Atiya Fyzee, who

visited Heidelberg in that period). She had little importance

to the biographers of Iqbal until the late 1980’s when the

poet’s letters to her emerged through a Pakistani research

tourist who subsequently gathered information about her family

too (Emma herself handed over the original letters to the Pak-German

Forum sometime before her death in the early 1960’s, but

that set was never heard of again). Emma’s replies to Iqbal

may have been lost to us along with some other private papers

destroyed by him near the end of his life.

From what we can gather now from the surviving

one-side of the correspondence, he did have some sort of emotional

attachment to her. An oral tradition runs in her family about

her wanting to leave for India sometime around 1907 and being

stopped by her brother. “I’ve forgotten my German,”

Iqbal wrote to her sometime after his return to India. “Excepting

a single word: Emma!”

Some business in Paris, about which we don’t

know anything, prevented him from making a return trip to Germany

on his way back to India and despite two more journeys to Europe

in the 1930’s, he was never able to revisit Germany or meet

Emma after those few blissful days in Heidelberg. She is quite

likely to have been the muse for those movingly romantic poems

from Iqbal’s stay in Europe that were once wrongly considered

to be inspired by Atiya Fyzee. However, the influence of German

romantics of a century ago should not be overlooked as a significant

source of inspiration too: Iqbal made acquaintance with their

thought during his stay in Germany. “Our soul discovers

itself when we come into contact with a great mind,” Iqbal

was to jot down three years later. “It is not until I had

realized the infinitude of Geothe’s [sic. Goethe’s]

imagination that I discovered the narrow breadth of my own.”

Changing attitudes

towards poetry

The

general contempt for the poet by a society who loved poetry cannot

be better illustrated by the fact that at one point its greatest

poet of the age decided to quit his craft for good, and even to

curb his frequent, irresistible and spontaneous overflow of emotions.

Fortunately, this shift took place away from the society whose

views would have condoned it and the matter was brought to the

attention of Thomas Arnold, who in London had resumed his mantle

of being Iqbal’s mentor. Mustering the willing suspension

of disbelief that was required to accept any likelihood of Iqbal’s

quitting poetry, he went on to convince the reluctant artist that

his competence was a boon to his nation, and his verses could

do wonders. The

general contempt for the poet by a society who loved poetry cannot

be better illustrated by the fact that at one point its greatest

poet of the age decided to quit his craft for good, and even to

curb his frequent, irresistible and spontaneous overflow of emotions.

Fortunately, this shift took place away from the society whose

views would have condoned it and the matter was brought to the

attention of Thomas Arnold, who in London had resumed his mantle

of being Iqbal’s mentor. Mustering the willing suspension

of disbelief that was required to accept any likelihood of Iqbal’s

quitting poetry, he went on to convince the reluctant artist that

his competence was a boon to his nation, and his verses could

do wonders.

The seriousness given to this incident by its narrator,

Sir Abdul Qadir, requires that we take it as another landmark

in Iqbal’s mental odyssey. He became more conscious of his

role as a seer and the obligation to use his verse mainly for

telling others of what he saw as the solution to their problems.

For nearly two and a half years after his return from Europe he

was still not prepared to be seen as a poet of any kind although

he couldn’t help composing a good poem every other month

– usually expressing some Islamic idea in his unique powerful

manner. However, his major focus was his legal practice –

which remains the most ill-researched area of his life. It does

seem, however, that even in this unsuitable profession he gained

some success, thanks to a penchant for hard-work that only a Victorian

could have possessed (and Iqbal was very Victorian in some ways).

This was contrary to the negative impression spread by his rivals

and epitomized in Justice Shadilal’s disqualifying comment

on his candidature for the bench of the Lahore High Court in the

1920’s, “We know him as a poet, but not as a lawyer”).

Meanwhile, the over-reacher in him turned to prose.

Hard times

The period from 1908 to 1913 is generally

seen as a dark phase in his life on his own authority. Tracing

the roots of agony to his decision to separate his first wife,

his family’s initial resistance to the idea or the temporary

misunderstandings after the marriage to Sirdar Begum, is only

a partial discovery of the truth. Other pieces must be added to

the picture.

Humanism could mean the elimination of the divine

from the human life, in which sense Iqbal deplored it. In another

way the term could mean a shift of focus to the human interests

and in that sense he welcomed the birth, or as he called it, “the

re-birth” of humanism in the Muslim World. “Personality

being the dearest possession of man must be looked upon as the

ultimate good,” he wrote in the private notebook Stray Reflections,

which he kept for some time in 1910. “It must work as a

standard to judge the worth of our actions. That is good which

has a tendency to give us a sense of personality, that is bad

which has a tendency to suppress and ultimately dissolve personality.”

There was the rub. Every journey begins by taking

into account, not only the importance of the destination but also

its distance from the starting point. Those who set out to discover

God by looking inside their own souls sometime have to first understand

how the human being is different from God in order to save themselves

from mistaking a shadow of their own mind as the Ultimate Reality.

The result is a temporary cynicism. “My friends ask me,

‘Do you believe in the existence of God?’” Iqbal

wrote in the same notebook. “I think I am entitled to know

the meaning of the terms used in this question before I answer

it. My friends ought to explain to me what they mean by ‘believe,’

‘existence’ and ‘God,’ especially the

last two, if they want an answer to their question. I confess

I do not understand these terms; and whenever I cross-examine

them I find that they do not understand them either.”

In the three prose pieces from this period of his

thought he speaks about Islam, the Prophet, the Divine law, the

Muslim community and the need for a great personality but nowhere

does he tell us what role, if any, does the Almighty play in this

order of things. That must not surprise us, because the community

as envisaged by him now was itself the apparatus through which

God dispensed the destiny of the humankind, as Iqbal was going

to explain in Secrets and Mysteries a few years later (which will

be discussed in the next chapter).

In the paper ‘The Muslim Community –

a sociological study,’ the society is given many attributes

that were reserved for the Divine existence in traditional Muslim

mysticism. For instance, the society is described here as the

real organism and the individuals almost like those micro-organisms

that reside inside a body but cannot exist on their own. He mentioned

some “recent biological research” that had proven

that even the life-spans of the individuals are determined by

the needs of the group-organism. He did not quote the source of

his information but over a year later the thought resurfaced in

the famous lines in ‘The Candle and the Poet’ where

he said: “The individual is sustained by the nation and

is nothing on its own; the wave is whatever it is in the ocean

and nothing outside it.” (Fard qayam rabt i millat sai hai,

etc). Was he going against the message of the greatest Sufi poets

such as Sanai, Attar and Rumi, or was he rediscovering their true

message that had become obliterated by the dust of time? This

was the questions which experts were going to debate among themselves

at least for a century.

In the same paper he proclaimed that the “Society

has, or tends to have a consciousness, a will and an intellect

of its own,” and that the individual mind was nothing but

a channel through which flows “the stream of mentality”

of the society, and therefore “the individual mind is never

completely aware of its own states of consciousness.” Again,

this was almost the equation that previously existed between the

limited human consciousness and the absolute knowledge of God

(of course, Iqbal made one slight difference by saying that certain

thoughts passing on through individual minds were conceded to

remain below the threshold of social sensibility).

That same unidentified “recent biological

research” is supposed to have revealed that “in the

successful group-life it is the future that must always control

the present; to the species taken as a whole, its unborn members

are perhaps more real than its existing members whose immediate

interests are subordinated and even sacrificed to the future interests

of that unborn infinity which slowly discloses itself from generation

to generation.” Perhaps this was in his mind when he said

in his famous ‘Prayer’ (1911): “Grant us to

see the signs of the impending doom; grant us to think of tomorrow

amid the confusion of today.”

“Society is much more than its existing

individuals,” he wrote. “It is in its nature infinite.”

Was this not how some mystics had described God in the light of

wahdatul wujud? They had maintained that the individual ego must

be renounced in a union with the divine and it should not surprise

us that Iqbal was suggesting that the individual ego must be annihilated,

not in the Absolute Ego, but in the collective ego of the community.

“The forces of Nature appear to respect

neither individuals nor nations,” he wrote. “Her inexorable

laws continue to work as if she has a far-off purpose of her own,

in no sense related to what may be the immediate interest or the

ultimate destiny of man.” Indeed, this was a bleak picture

of the universe. True, it is illuminated by a eulogistic description

of the human capabilities (“Man is a peculiar creature.

Amidst the most discouraging circumstances, his imagination, working

under the control of his understanding, gives him more perfect

vision of himself and impels him to discover the means which would

transform his brilliant dream of an idealized self into a living

actuality”). However, this description of the human being

lacks an explicit statement of its Divine origins that was found

in the Al-Jili thesis and was later restored in Secrets and Mysteries.

It is not surprising that in this temporary phase

his perception of the Muslim culture is more earth-rooted than

elsewhere. The Muslim culture – and not only the faith of

Islam – must be adopted although he confesses that historically

this culture was influenced less by the Arabian inspiration and

more by the pre-Islamic heritage of Persia. Yet, “to the

Royal family of Persia, the loss of Persia’s political independence

would mean only a territorial loss; to the Muslim culture such

an event would be a blow much more serious than the Tartar invasion

of 10th (sic. 13th) Century.”

Difference of opinion could not be seen as something

to be upheld for its own sake. Chaos and confusion could dilute

the “organic unity” of the group-organism, something

so vital for its survival (and individuals could not exist independent

of their communities). “Islam is one and indivisible; it

brooks no distinctions in it,” Iqbal had called upon his

listeners in the 1909 session of Anjuman Himayat-i-Islam and condemned

religious and social sectarianism in the name of God, humanity,

Moses, Jesus Christ and the Last Prophet: “Fight not for

the interpretation of the truth, when the truth itself is in danger.”

Can truth ever be in danger? Two years later Iqbal

was going to discard his fears by saying that Islam could not

perish by the fall of Persia. However, the universe presented

a more depressing picture from where he was standing at the moment

and if this had not been the case, his personal problems would

have also appeared more tolerable to him. “As a human being

I have a right to happiness,” he wrote to Atiya Fyzee in

1909 while rambling over his desire to get rid of his first wife.

“If society, or nature, deny that to me I defy both. The

only cure is that I should leave this wretched country forever,

or take refuge in liquor which makes suicide easier. These dead

barren leaves of books cannot yield happiness; I have sufficient

fire in my soul to burn them up and all social conventions as

well. A good God created all this, you’ll say. Maybe, but

facts of this life, however, tend to a different conclusion. It

is intellectually easier to believe in an eternal omnipotent Devil

than a good God.”

In a Persian ghazal written around the same time

(but published much later in The Message of the East) he addressed

his Creator, “A hundred worlds bloomed from the fields of

my imagination, like flowers; You created only one, and that too

with the blood of our longing.”

Unlike Kant, Iqbal could not find it sufficient

to believe in God just because it was expedient to do so. Like

an offended lover he asked His Creator to answer some questions,

and indeed those were some difficult questions he penned down

in that season of his discontents, the winter of 1910–1911.

‘The Complaint’

Despair, anger and hope were catalyzed by the political

disappointments in the world of Islam (especially Iran and Turkey)

and distilled under such pressure in his otherwise optimist mind

that they found catharsis through his greatest poem so far (and

the most famous ever), ‘The Complaint’ (Shikwah).

“Your world presented a strange sight when we arrived on

the scene,” Iqbal ventured to remind his Creator, and went

on with a succinct description of pagan religions and how the

armies of Islam crushed them. Today, however, the bounties of

God were bestowed exclusively upon the non-believers while the

Muslims were destitute and humbled. “Shifting your affections

between us and our rivals every now and then?” Iqbal treaded

close to disrespect. “I dare not say it, but indeed you,

too, are such an inconstant lover!”

What prevents the poem from becoming disrespectful

is the deep emotional bonding between the human soul and its Creator,

and a remarkable absence of personal arrogance. Strictly speaking,

‘The Complaint’ is a prayer: “Allow the song

of this solitary nightingale to pierce the hearts of the listeners,”

Iqbal eventually comes to the point after his long detour of slants

and sarcasm. “Let this caravan bell wake up the hearts from

deep slumber to be refreshed with a new covenant, thirsting after

the same old wine; Oh, what if my glass is of Persian origin,

the wine I have to offer is none but Arabic; Oh, what if the song

I am singing is Indian, the tune I render to it is none but Arabic.”

The poetic landscape of ‘The Complaint’

is deceptive if studied in isolation from the prose works. The

onward march of sword-swashing Arab warriors may be effective

poetic imagery but it stands in variance with Iqbal’s own

contention that territorial expansion serves as handmaid to tyranny

and that the Arab imperialism was a disservice to Islam –

something he was asserting forcefully in his lectures delivered

around the same time and emphasized it again in his famous Presidential

Address in 1930 where one of the very reasons why he proposed

a modern Muslim state in India was that the Muslim politics might

stand a chance of developing on lines different from the ones

adopted in the past. However, a complete argument could not have

appeared in ‘The Complaint’ without disrupting the

unity of thought so essential to a poem. Yet, the answer he wrote

to his own poem within a year by the title of ‘The Candle

and the Poet’ suggests that the causes of political decline

among the Muslims were not that they had become unwilling to fight

but rather that they had stopped looking within. Another sequel

by the title ‘The Answer’ (Jawab-i-Shikwah), which

was written still a little later, balanced the imagery of ‘The

Complaint’ with the imagery of rationalism and contemplation:

the Muslim World is in a bad shape because there are no more Ghazalis

in it.

All said and done, ‘The Complaint’ takes

a steep departure from conventional devotion by opening a discourse

on God from the human point of view; the duality between our attitude

to the world and our attitude to God withers away as we approach

the Divine altar without taking off the cloak of human sentiments

and basic instincts.

On a personal level, ‘The Complaint’

must have provided a much-needed catharsis to him because after

writing it he became willing to be seen as a poet once again.

Then, soon afterwards, he embarked on the fulfillment of his primordial

dream: a formula for global prosperity.

transformation

The first impediment in the way of human happiness

was the fragmentation of humanity into interest-driven groups.

The grouping took place, according to Iqbal, not on the basis

of class-conflict as suggested by Marx, but on the basis of reduced

identities. In the past these false identities were the various

idols, which were fortunately not revered anymore (he didn’t

count the Hindu deities among idols but interpreted them as somewhat

transformed notions of angels). However, the modern times presented

the humanity with new impediments instead of the old ones, and:

“chief among these fresh idols is ‘country,”

he unfurled his banner in the poem ‘Patriotism – or

country regarded as a political ideal’. And hence he decided

that it was his aim “to discover a universal social reconstruction.”

Religious belief could serve as an antidote

against parochial grouping of humanity by uniting the human with

the Divine and creating a universal bonding through the unity

of the Creator. All religions lead to the same destination but

it seemed to Iqbal that Islam was a suitable starting point in

the modern age, since, unlike Hinduism and Judaism, it was not

a racial belief and unlike Buddhism and Christianity it didn’t

turn its back on the material world. The idea that Islam offered

a model for a universal citizenship had settled in his mind while

he was in Europe where he ecstatically sang in a ghazal: “That

Arabian architect gave it a unique construction: the fortress

that is our religion is not founded in the unity of the homeland.”

Some initial conclusions drawn out of this otherwise

sound principle may sound outlandish today. In his 1909 lecture

he declared that since the political ideal of Islam was democracy

and the British Empire was democratizing the world therefore the

British Empire was a “Muhammadan Empire.” Apart from

any psycho-logical relief that he must have found in seeing a

brighter side to the British subjugation of India, he actually

believed that the Muslims were not the only followers of Islam.

In the poem ‘The Answer’ (1912), the Divine Justice

bestows the rewards of the Muslims upon heathens who have become

Muslims in practice even if not in name. Likewise, towards the

end of his life he stated in a conversation that all truth is

an interpretation of the Quran even if it comes from an atheist,

or from someone like Lenin. Islam, in the mind of Iqbal, was not

a monopoly whereby some self-righteous persons should sit in judgment

upon the spirituality of the others. “God is the birthright

of every human being,” he said in another writing.

Somewhere along the way he outgrew his late anxieties

over the plight of the Muslim World. “You will not perish

by the fall of Iran,” God informed the Muslim complainant

in ‘The Answer’ (1912). “The effect of the wine

doesn’t depend on the cup in which it is served.”

This was the transformation famously mistaken as

his shift from “nationalism” to “Islamism.”

His concern remained the humanity, always. His interest in Islam

was also heavily focused on doing something for the human race

through the undiscovered wisdom of this religion. “The nations

of the world remain unaware of your reality,” God tells

the Muslims in ‘The Answer’. “The world still

needs you as you are the warmth that keeps it alive and your mantle

is the ascendant of the Possibility’s destiny. It is not

the time to rest and relax, for work still remains; it still remains

to culminate the light of Unity.”

Ironically, it was just the time when the Muslim

masses in India had been roused for the first time by Shibli and

his disciples, including Maulana Muhammad Ali (“Jauhar”),

to join hands with the Congressional patriots to construct a regional

identity. Iqbal didn’t openly criticize them; such criticism

would have defeated its purpose and would have been mistaken as

a service to the divisionary policies of the colonial rulers.

However, the fact that he wrote his most bitter criticism of regional

patriotism in those same days is a sufficient indication of his

views.

The settling down

1913 was the year when Iqbal settled down. His domestic

life acquired a blissful character after separation from the unfortunate

first wife and consummation of two more marriages (although he

would have been content with only one, if the strange bent of

circumstances had not forced him to take two – he wrote

in a private letter). It was also the year when he was offered

a generous stipend by an extremely cultured patron – Maharajah

Kishan Prashad, the Prime Minister of Hyderabad (Deccan). The

offer, which would have been accepted by any poet of the old school

as a natural order of things and bought him endless time to spend

for creating masterpieces, was respectfully but firmly declined

by Iqbal. He was a poet of the new order – perhaps belonging

to an age that was yet to be born.

This decision was taken by him around the same

time when he was beginning to write down a long Persian poem about

the most important issue in the human life: ‘The Secrets

of the Self.’

Previous

| Contents | Next

|