|

Search the Republic of Rumi

|

|

|

|

Chapter

3

The Illumination (1914-1922)

|

Secrets and Mysteries

Thirteenth Century scholar Maulana Jalaluddin

Rumi was lecturing his pupils when he was interrupted by a wandering

dervish Shams of Tabriz, who pointed at the books and asked what

they were. He was met with sarcasm by the irritated scholar: “Something

you would not comprehend.” Presently, Shams threw the books

into a nearby pond and when Rumi was devastated on their loss

he took them out, dry and unharmed – or, according to another

variation on this parable the dervish burnt the books and later

restored them from the ashes. In either case, when Rumi asked

him in disbelief what was it he had done, the dervish returned

him his own words, “Something you would not comprehend!”

Rumi fainted and found himself a changed man when he recovered

several days later.

This historically unreliable anecdote contains

a candid metaphorical approximation of what might have happened

when Rumi met Shams who was to become his master. The passage

from knowing to witnessing is indeed nothing less than a miracle

and requires a master to perform it for the disciple. The master

who came to Iqbal’s aid was, remarkably, none other than

Rumi himself. For it is said that Iqbal dreamed that the master

was asking him to write a masnavi. “You command us to negate

the self whereas it appears to me that the self ought to be strengthened,”

Iqbal protested in this dream. “The meaning of what I say

is not different from what you understand,” said the mysterious

Sufi before Iqbal woke up to find himself inspired for writing

his own masnavi.

He intended three volumes of this masnavi, which

was eventually going to be called Secrets and Mysteries (Asrar-o-Rumooz).

The first part would define the source of all good in the practical

world: the human ego, or the self, receiving its illumination

from the Absolute Reality and in turn illuminating all areas of

human existence. The second part would explore the relation between

the individual ego and the society, and how an ideal nation could

emerge from the combined will of enlightened individuals. The

third and the final volume would describe the future history of

one such nation, the Muslims.

The human possibilities, Iqbal thought, were as

yet unexplored and he truly believed that his message was derived

from those meanings of the Quran that were awaiting the modern

times to be fully realized. Little did he imagine that he would

soon be accused of muddling the stream of religious thought with

greed and egotism.

The self-perception of being alone, and unique,

made it easy for Iqbal to see himself as a poet from another time

and space: a poet of tomorrow. It liberated him from his world

so that he could open himself to what he would frequently describe,

in various ways, as the source of life itself. What he later said

of some contemporaries was equally true of him too: “Such

men are liable to make mistakes. But the history of nations shows

that even their mistakes have sometimes borne good fruit. In them

it is not logic but life itself that struggles restless to solve

its own problems.” It is this “connectedness”

that makes Iqbal sound so contemporary in the 21st Century.

“Life is but a manifestation of the selves,”

he opened the first chapter of his book after the prelude, “Everything

you see is counted among the secrets of the self.” The self

(or the ego) is the creator of its own opposites, it manifests

itself through power, strife, love, life and death – hence

in one sweep Iqbal flies through anonymous allusions to Hegel’s

philosophy and Nietzsche’s will to power, and arrives beyond.

However, the self is none of these and more – the references

to these attributes are merely figures of speech comprehensible

to the readers. The point Iqbal really wants to make is that whatever

we know about life and the universe, whether we know it through

science, religion or metaphysics, eventually boils down to one

basic fact: by strengthening the ego you live; through its renunciation

you perish. True and lasting expansion does not come from invading

the space of others; it comes from growing stronger in oneself.

The principle of growth is inward-out, not out-and-out. The seed

contains the stem in it, and likewise by nurturing the fountainhead

within and not by envying the power of others a human being grows

stronger.

Thinkers who aspire to present a coherent picture

of the world often take off by focusing on one issue as a starting

point and the central problem to Iqbal, in life as well as thought,

remained the nature of love. Here, he tried to make sense of this

ultimate madness, i.e. love. If there were no “others”

in the world and no distances, no pangs of unrequited feelings

(and the spurns), then there would have been no desire; and desire

is to the ego what fuel is to an engine and water to all living

things. Desire is the lifeblood of the ego. Rumi started his masnavi

by saying that the music of the flute was nothing but the reed’s

cry in pain over separation from its source. Iqbal ventured to

show, rather boldly, the other side of the coin: the flute became

what it was by separation from its source. True, the separation

is virtual rather than real (and Rumi had already pointed out

that the music is coming from the breath of the player and hence

there is no distance between the two ends of the flute). Iqbal

accepted Rumi’s perception of the Divine origin but went

on to state that separation had its own virtues: in a perfect

union things would turn to nothings.

The anatomy of desire is usually seen as comprising

of love and begging. Iqbal was probably right in claiming that

he was unraveling the secrets no one else dared reveal in the

East: he was pointing out that love and begging were the opposites

of each other and you could only choose one of these two. Love,

in its essence, is the tool through which the ego elevates itself

above the impediments of the physical world; love could teach

rebellion to the humblest creatures. “The hardest rocks

are shivered by Love’s glance,” said Iqbal. “Love

of God at last becomes wholly God.” Asking, however, dissociated

the ego from its Divine source of illumination.

Naturally enough he deplored the literature that

followed conventions of self-negation and perpetuated a distorted

image of love that equated desire with beggary (it was Iqbal’s

criticism of Hafiz in the first edition of ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’

that raised the storm of protest in 1915). Iqbal also criticized

Plato, as should be expected from someone whose position on the

reality of the physical world and the significance of “purpose”

in defining things was in a direct line of inheritance from the

man who said that A is A (Iqbal’s dislike for being labeled

would prevent him from wanting to be seen even as an Aristotelean;

in his notebook he jotted down difference with the Greek philosopher

over a non-issue after admitting agreement on the basics).

In his characteristic spirit of ruthless objectivity

Iqbal glorified Time, which to him was neither a sequence of day

and night, nor just another dimension of space, but was nothing

less than a Divine manifestation. “Do not vilify Time, for

God says ‘I am Time,’” the Prophet had told

his followers. With this remarkable hadith, Iqbal also used a

quotation from Imam Shafii by way of further explanation: “Time

is a sword.” One who reads the signs of the Time instead

of finding faults with it is the one who masters all difficulties.

Escape from Time is lethal – and here we may add that nostalgia

for the past and unrealistic wishes for the future are two chief

examples. The ego needs to discover a symbiotic relationship with

the sublime energy that is Time.

Moving from the general to the specific, Iqbal

highlights the love his Muslim readers carry for the Prophet,

and shows them that the education of the Self has three stages:

(a) obedience; (b) self-control; and (c) the divine vicegerency.

The purpose of the Muslim’s life was to exalt the Word of

God. Jihad, if it be prompted by land-hunger, was unlawful in

the religion of Islam.

Iqbal perceived this wonderful creation, the individual,

to be an organic component of the larger social organism. The

society was an ego too, he propounded in ‘Rumooz-i-Bekhudi’,

the second part of his masnavi. The individual finds an everlasting

strength by submerging his or her ego into that of the nation.

The Muslim nation was independent of time and space, and its eternity

was promised (unlike the individual, whose immortality was only

conditional). The two fundamental principles of this nation were

monotheism (which cured fear and despair, the two spiritual diseases

fatal to the ego), and prophet-hood (which aimed at providing

liberty, equality and fraternity to the human race).The nationality

of Islam, fortunately, was based on the principle of equality

and freedom (in the proof of which Shibli had left behind enough

anecdotes from history before dying in November 1914, when Iqbal

was still working on the first part of the masnavi).

What is more significant is that Iqbal provided

an alternate position on the relationship between the individual

and the society, rooted in love and like-mindedness rather than

whim or racist principles.

The idea of the individual ego merging into the

larger ego of the community was a movement of growth: one cannot

achieve alone what many can achieve together, as we are now realizing

through such concepts as synergy and teamwork in management sciences.

What could not be achieved in the world if the entire human race

could turn into a like-minded creative whole?

The battle for God

|

|

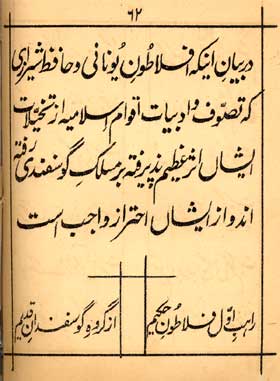

| Above. The

first edition of 'Asrar-i-Khudi' (1915) contained some harsh

criticism of Plato and Hafiz. On further reconsideration,

Iqbal changed his opinion about Hafiz but remained a lifelong

opponent of Plato, making it his mission to detox the literature

and spirituality of the East from the negative influence of

the Greek philosopher. |

Back in 1910 he had made a mental note on

shifting the focus of the Eastern metaphysics from the existence

of God to the existence of the human being. The anatomy of the

human ego presented in ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’ was glowing

with the light of the Divine Existence. “I have conceived

the Ultimate Reality as an Ego,” he later wrote. “From

the Ultimate Ego only egos proceed.” Individuality implies

finitude, and although he did not raise the issue in ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’,

he addressed it boldly many years later in The Reconstruction

of Religious Thought in Islam. “The Ultimate Ego is... neither

infinite in the sense of spatial infinity nor finite in the sense

of the space-bound human ego whose body closes him off in reference

to other egos. The infinity of the Ultimate Ego consists in the

infinite inner possibilities of His creative activity of which

the universe, as known to us, is only a partial expression. In

one word, God’s infinity is intensive, not extensive.”

Other important elements in his conception of God,

from the intellectual perspective, would be later named as Creativeness,

Knowledge, Omnipotence and Eternity. In each of these God is superior

to, and inestimably different from, the human being, since the

universe and reality is not an ‘other’ to Him. “The

Absolute Ego... is the whole of Reality,” Iqbal would state

in The Reconstruction. “The perfection of the Creative Self

consists... in the vaster basis of His creative activity and the

infinite scope of His creative vision.”

Iqbal’s position on Sufism has long constituted

a controversy in the study of his thought, beginning with ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’.

The preface to the first edition denounced wahdatul wujud (which

was subsequently translated as pantheism in his English writings).

Some of his detractors would later point out that like his predecessor

Shiekh Ahmad Sirhindi, who had done the same in the early 17th

Century, Iqbal could not access the original writings of Ibn ‘Arabi

to whom the popular opinion ascribed the origin of wahdatul wujud,

and his adolescent familiarity with The Bezzels of Wisdom was

far from an ideal starting point for an understanding of Ibn ‘Arabi.

According to these detractors, Iqbal, like the early Orientalists,

ignored the fact that wujud in Arabic had the same root as wajdan

(intuition) and carried a second meaning of “finding”;

such connotations were tragically lost through translation as

“the unity of being” or “the unity of existence”,

and to equate it with pantheism (as Iqbal did) was a great blunder.

Whatever may have been the meaning of wahdatul

wujud for Ibn ‘Arabi and his inner circle, the corrupted

usage of this term, which came to prevail in India at least as

early as the days of Sirhindi, was nothing less than a justification

used by the handful of the ruling Muslim elite for the weakening

of their nerves (which was an unavoidable consequence of the sustained

activity of empire-building for almost a thousand years). Wahdatul

wujud became a convenient euphemism which could be used for just

any excuse for procrastination, lack of determination or inaction

on any given occasion. Hence the couplet of a Pathan poet, aptly

quoted by Iqbal in a hostile essay: “I used to turn away

armies in the battlefield but ever since I became familiar with

the wahdatul wujud I squirm away even from breaking a straw since

it might hurt God (since the Almighty was supposed to be existing

in everything according to the corrupted usage of this doctrine).”

Whether or not Ibn ‘Arabi would have been shocked at this

blasphemy, there was no way for Iqbal to be sure that the Spanish

mystic was not the original perpetrator of such attitudes. Consequently,

although Ibn ‘Arabi was spared slants in the poem itself

he was shown no reverence in table talk and correspondence for

some time. “The Bezzels of Wisdom used to be taught at my

father’s house while I was growing up,” Iqbal wrote

in a letter. “From what I know, it contains nothing but

atheism and impiety.” This view was changed afterwards and

reverence was restored to Ibn ‘Arabi.

Hence it should not surprise us that while Iqbal

denounced wahdatul wujud, he was also the most eloquent mouthpiece

of some of its aspects at the same time. Mir Dard included, the

entire repertoire of mystic poetry in Urdu may not furnish a single

example to outdo this remarkable couplet from Bal-i-Gabriel (1935):

“This is the gist of what the qalandars know: life is an

arrow spent and yet never far removed from the bow.” Another

couplet from a Persian ghazal gives us a remarkable analogy for

the distance (or closeness) between the human being and its Creator:

“Between me and Him is the equation of the eye and the sight,

for one is with the other even in the greatest of distances.”

Critics have found difficulty reconciling such expressions

with his well-known stand against wahdatul wujud, and the most

convenient alibi is, of course, to say that Iqbal had yet another

change of heart some time after writing ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’!

One way of avoiding such melodramatic explanations is to say that

Iqbal, like most of his contemporaries, confused two different

concepts: the wahdatul wujud as experienced by Ibn ‘Arabi

and the greater mystics, and the wahdatul wujud as perceived by

the decadent Muslim societies of the later period; hence he believed

that both were the same, and criticized both, but inner life discovered

and retained a contact with the Divine illumination which, whether

he knew it or not, was directly in line with the original Sufi

connotations of wujud. Another way of looking at things could

be to presume that just like his predecessors Shah Waliullah and

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Iqbal had also been able to catch the glimpse

of something outside the speculative debates of theology, and

was speaking from a different milieu altogether.

All said and done, most mystics (including Rumi,

according to some), favored union over separation. Union was a

blessing while separation was a curse: the drop becomes the ocean

itself by becoming a part of it. According to Iqbal, however,

the drop should lodge itself in an oyster and become a pearl.

“The wave, so long as it remains a wave in

the sea’s bosom makes itself rider on the sea’s back,”

he stated in ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’ (The same imagery had

been used earlier in ‘The Candle and the Poet’ (1912)

to illustrate the dependence of the wave on the ocean). From a

traditional mystical position this sounds like an affront to love.

However, this is just another point where Iqbal seems to be in

touch with the pulse of our times even more than that of his own.

Today, the society itself seems to be imposing the mixed blessing

of personal space on individuals – the large percentage

of broken marriages and an increased number of people, women included,

who opt for living single are already being interpreted by some

observers as a change in the patterns of personal growth in the

modern world. Added to this is the general observation that most

citizens today insist on determining their obligations towards

the society without compromising on their own individuality.

Mysticism had a unique role in the East where the

traditional society was polarized between the court and the shrine.

In the absence of political movements the shrine provided catharsis

for the socially oppressed classes as well as for any non-conformist

drop-outs from the elitist circles, such as the aristocratic Ameer

Khusro and the Mughal prince Dara Shikoh. Obviously, this was

also a safety valve that prevented the masses from questioning

the roots of oppression. Iqbal appeared at a time when this non-questioning

character of the Eastern society was changing due to contact with

Western political thought and it was therefore inevitable that

his interpretation of the tradition, no matter how mystical, could

not be in full conformity with the past. In that he was guided,

fortunately, not so much by logic but more by what he termed as

“an inner synthesis of life.”

Beyond his own age Iqbal was also criticized by

that breed of post-colonial scholars who is best represented by

Syed Hossien Nasr and his circle – a new type of scholarship

about which it is yet to be decided whether it represents the

perspective of the West or the East, or some other perspective

developed in the isolation of academic covens. Their main accusations

against Iqbal are that he was a Darwinian and departed from the

traditional Muslim thinking. Such accusations are probably rooted

in a general perception that prevails in the Western academia

(and was evident even in the days of Iqbal), according to which

the East is not capable of offering any original thought in our

own age. Anyone who shares this bias is invariably doomed to measure

Iqbal by the parameters already known in the academic circles

of the West. The pre-requisite for understanding Iqbal seems to

be a willingness to grasp a new worldview, and despite their tremendous

profundity and scholarship, Nasr and his school have not yet shown

this kind of willingness. It would probably suffice to say that

while Iqbal had an adequate respect for the old, he also committed

to the value of human growth. To him, the humanity was developing

like a single organism, and the differences between cultures were

to be used for empowerment of the people, and not to be idolized

pseudo-identities: “Give up not on the East, nor shun the

West when the Nature itself signals you to turn every night into

a bright morning,” was his message.

The Poetics of Iqbal

|

|

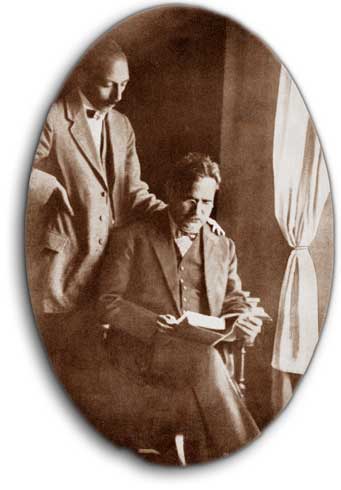

Above:

Iqbal with his friend Nawab Sir Zulfiqar Ali Khan,

who wrote the first monograph on the poetics of Iqbal, A

Voice from the East (1922). |

Considerable portion of ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’

was devoted to the philosophy of art, especially literature, and

this theme recurred in many subsequent writings – most notably

in ‘The Book of Slaves’ in Persian Psalms(1927) and

Zarb-i-Kaleem (1937). All such views taken collectively form a

kind of poetics of Iqbal, and may be approached from two aspects:

firstly, the psychology of creation; and secondly, the aim of

art and literature.

So much has been written about Iqbal’s lofty

ideals in arts that it is very often forgotten how much importance

he placed on the basics. The craft is important. Iqbal himself

mastered the classical skills of poetry while still at school.

These included the science of metre, numerology of alphabet and

the rules governing various genres. The medieval tradition of

apprenticeship held these rules as inviolable and there was a

degree of truth in that belief: the rules of any art are not made

by the masters but discovered by them. They are just like the

laws of nature; you need to discover the laws governing gravity

if you want to make an aircraft. Likewise, you need to understand

the effect of language on the listeners if you wish to move them

with your poem. It is true that the poet may be inspired with

an idea that is difficult to be expressed through conventional

manner of writing. However, it is the destiny of a true artist

to struggle against the scientific laws of his or her craft, so

that the great idea becomes more than an idea – so that

it becomes a piece of art that can appeal not only to the mind

but to the entire being of the audience. It was with reference

to these labors and rigors that Iqbal later said in The Blow

of Moses (1936): “Although the invention of

meaning is nature’s boon, yet from striving and struggling

the craftsman cannot be free. By the heat in the mason’s

blood does it take its life: be it the tavern of Hafiz or the

temple of Behzad! Without persistent labor no talent reveals itself,

for the house of Farhad is illuminated by the sparks of his spade.”

The first criterion for any piece of art, therefore,

is perfection. It should be beautiful, grand and pleasing. It

must give pleasure. However, since ego is the most cherished value

in life, a piece of art must also aim at strengthening the ego

and not at weakening it. “Thus the idea of personality gives

us a standard of value,” he wrote in his explanatory notes

to Nicholson when the latter set out to translate ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’

a few years later. “That which fortifies personality is

good, that which weakens it is bad. Art, religion, and ethics

must be judged from the stand-point of personality. My criticism

of Plato is directed against those philosophical systems which

uphold death rather than life as their ideal – systems which

ignore the greatest obstructions to life, namely, matter, and

teach us to run away from it instead of absorbing it.”

It is here, in his theory of art, that Iqbal comes

closest to Aristotle (a point often ignored). His concept of art

rests heavily on assumptions such as A is A, contradictions do

not exist, purpose defines the object, and growth is a central

value in life – basic Aristotelian dictums. It is quite

likely that although he was acquainted with Aristotle’s

writings too, he absorbed these ideas more passionately through

the works of such Muslim poets as Nezami Ganjavi and Abdur Rahman

Jami among the old, and Maulana Hali among the new, who had written

extensively on the philosophy of verbal art – and, quite

possibly, also those classical Muslim thinkers who had reinterpreted

Aristotle in the light of the ideals of Islam. Similarities between

Iqbal and the American author Ayn Rand (1905 – 1982), although

extremely superficial, may still present a laboratory test on

how far Iqbal’s literary views were enriched by the Aristotelian

current in the Muslim thought as well as the Romantic Movement

of the West. Iqbal and Ayn Rand never admitted of hearing about

Iqbal (which casts a somewhat undesirable shadow on her scholarship),

but some of her propositions sounded like literal translations

of Iqbal when it came to defining the purpose of art. Rand described

art as “the technology of soul” and the means for

the human being’s “psychological survival.”

Passages from The Romantic Manifesto (published as a book in 1971,

but dating back to the 1950s), could easily pass for Iqbal’s

own words if one didn’t know better: “Since man’s

ambition is unlimited, since his pursuit and achievement of values

is a lifelong process – and the higher the values, the harder

the struggle – man needs a moment, an hour or some period

of time in which he can experience the sense of his completed

task, the sense of living in a universe where his values have

been successfully achieved. It is like a moment of rest, a moment

to gain fuel to move further. Art gives him that fuel. Art gives

him the experience of seeing the full, immediate, concrete reality

of his distant goals.” It is quite interesting to notice

that Rand deplored the influence of Plato on the intellectual

life of the West while Iqbal deplored the same in the East. The

only plausible reason for such similarities could be their common

interest in Aristotle.

The unwritten

The third part of the masnavi, which

was supposed to describe a history of the future, got delayed

for some reason. There are two possible explanations. The first

is that after writing the second part, his poetic inspiration

took a much more lyrical bent, and compelled him to turn to allegories

such as the Urdu poems ‘Khizr of the Way’ and ‘The

Dawn of Islam’, and the Persian anthology Zuboor-e-Ajam

(to be discussed in the next chapter). However, he eventually

described the basic principles of the destiny of nations in his

last Persian masnavi, What Should Now Be Done? (1936), which answers

many questions that might be asked at the end of Secrets and Mysteries.

“You know very well,” he says in What

Should Now Be Done?, “Monarchy is about the use of brute

force. This brute force, in our own times, is commerce. The shop

is now an extension of the throne: they acquire profit through

commerce and tax through kingdom.” He advises the Eastern

nations to strengthen their self-esteem by drawing upon the healthy

traditions of the past, and by attaining economic independence.

He insists that healthy personalities cannot develop without political

independence, and he explains that political wisdom is either

divinely inspired or diabolic. The divinely inspired political

wisdom liberates, like Moses; the diabolical political wisdom

enslaves, like the Pharaoh.

Another explanation could be that he embedded the

unwritten history of the future in all the works which he wrote

after Secrets and Mysteries. For obvious reasons, such a proposition

sounds fanciful and may require a separate book in order to be

fully explored – possibly a book very different from the

present one.

“The object of my Persian poems is

not to make out a case for Islam,” he stated to the Western

audience at one point. “My aim is simply to discover a universal

social reconstruction.” He went on to explain why it was

philosophically impossible to ignore a social system that met

this ideal of combining matter with spirit. He might have also

seen the religious belief as a useful latent resource for mobilizing

the people. If they were willing to die in the name of faith then

there must be no limit to the wonders they could achieve if their

faith was reinterpreted as a recipe for “universal social

reconstruction.”

However, this approach was not without its fatal

drawback and with our knowledge of what happened to his message

after his death we can see the irony more clearly than he might

have anticipated in his own times. If he were expecting that the

masses would jump with a pleasant surprise at finding a more liberating

interpretation of their ancient beliefs then he was obviously

overlooking those countless numbers to whom religion wasn’t

necessarily a tool for self-actualization but rather a convenient

escape from critical thinking.

This was evident in the reaction to his poems. The

first appearance of ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’ was met with a

widespread outrage but criticism was restricted to the author’s

irreverence to Hafiz and his dedicating the poem to a controversial

personality. Virtually nobody questioned the main argument of

the book or asked the author whether his philosophy was practicable

or not, whether it was based on fact or delusion; people were

not bothered about the truth of what he was saying, they were

merely concerned with its propriety. Once the storm subsided,

his former reputation as a poet of Islam was remembered and in

fact, new colors added to it. Then the balance tilted in the other

direction with an equal sway of emotion: his works were scanned

to pick up references to Muslim kings and warriors until those

few and sparse verses where he had glorified the past became his

best known lines. Mercilessly taken out of their context they

were printed on calendars and banners in his lifetime and ever

since, and serve as fuel to whatever direction the mass hysteria

takes at any given time. Holistic view of Iqbal’s message

has been rare while the real worth of his poems perhaps still

lies undiscovered – as he himself prophesied at the beginning

of ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’: “My own age doesn’t

know the secrets; my Joseph is not for this market… Many

a poet there has been who are born after they die, opening our

eyes while closing their own; like flowers they sprout from the

soil of their tombs.”

Political correctness is one issue that seems very

relevant here. Indeed, Iqbal is held in such reverence in his

own country that the idea of apologizing on his behalf is understandably

offensive to many. It must be remembered, however, that he himself

was quicker than most thinkers in responding to ever new manifestations

of reality and even when he had to retract from a previously held

proposition he did so not with a grudge or dismay but with an

almost childlike fascination at finding the possibility of a new

position. This is what he did throughout his life and this is

what he might have wanted to do even after his death: he even

anticipates growth in the grave when he mentions that like flowers

some poets sprout from the soil of their tombs. How would he modify

his propositions if he were living in the 21st Century? This question

cannot be irrelevant to the legacy of an immortal thinker and

can be answered at least in some parts if we distinguish his thought

from analogy, principle from example.

One such issue is Iqbal’s position on the

women’s role in society. ‘Rumooz-i-Bekhudi’

doesn’t finish without ‘An Address to the Maidens

of Islam,’ in which the poet emphasizes the importance of

motherhood in ways that sound today like a denial of the woman

as an individual in her own right. Indeed it might be so, but

we must remember that neither England nor America had granted

its women the right to vote by that time. In stating the views

that he stated in his writings, Iqbal wasn’t being backward

but only taking sides with a large section of men and women throughout

the world who feared that women’s equality with men could

not be translated into practice. That the world didn’t come

to an end when the women eventually started participating in political

life is such an obvious fact that it is hard to believe that Iqbal

would have missed it if he was living in our times. That he advocated

many social rights for women in his later life (which will be

discussed in their proper place), is a reassurance to this, if

needed.

World War I, and the aftermath

The First World War (1914-1918) began while

Iqbal was writing the first part of his poem, and ended after

the publication of the second. The Russian Revolution came in

the meanwhile, and afterwards, Gandhi’s non-cooperation

tactics (including the great Khilafat Movement of the Muslims

of the sub-continent). Iqbal gave two cheers to the first, and

perhaps only one to the second. He was obviously delighted to

see the uprising of the downtrodden against an oppressive system

in Russia, but communism was alien to his fundamental thesis that

the nature of reality is essentially spiritual and the human capability

grows organically from within to master the physical world. Iqbal

was moved, not by the ideology of the Bolsheviks but the earth

shattering cry of freedom that came from the throats of millions

in a grand unison during that Red October.

Gandhi’s heroic defiance of the British imperialism

also won some versified praise from Iqbal (which remains half-forgotten

today, since it was later kept out of his collected works). However,

just as the Bolsheviks had denied the spiritual principle in the

name of modern technology, Gandhi apparently denied modernity

in the name of some spiritual principle that was only partially

revealed to him yet, and his followers were promised to be updated

periodically when and as, and if, the guru’s inner light

illuminated him. Iqbal joined the Khilafat Movement initially

but quitted it over disagreement on constitutional procedures

– the Khilafat leaders were well-known for being driven

by a noble expediency that often made them incapable of fulfilling

rational requirements (and it is interesting to recall that Jinnah

also dissented from the Indian National Congress around the same

time over similar disagreements with Gandhi).

‘Khizr of the Way,’ the Urdu

poem Iqbal recited in 1922, captured his appraisal of the current

affairs and in some ways summarized the contents of the third

part of his Persian poem, which was very much on his mind at that

point but he was delaying its writing (and the composition of

an exhaustive Urdu poem could be one reason why he was left without

the appetite to revisit the subject even in Persian too soon).

Khizr, the traditional ever-living guide of Islamic

folklore, gives a quick recap of the principle of movement and

existence – as if for the benefit of those who might have

missed Iqbal’s longer Persian dissertations on the subject

– and then comes to three crucial issues: imperialism, capital

versus labor, and the Muslim world.

“Imperialism is sorcery of the dominant nations,”

the old sage speaks through Iqbal, and euphemistically criticizes

the recent constitutional reforms of the British government as

mere eyewash. Through Khizr’s salute to the Russian people

in another section of the poem, Iqbal comes out as most magnanimous:

he goes to the extent of defending the Bolshevik philosophy against

his own spiritual principle. “The human spirit broke free

of all fetters,” says Khizr. “After all, how long,

could Adam weep for a lost paradise?”

References to the current situation of the Muslim

world in this poem are, simply, poetic expression at its best.

“The sons of the Trinity took away the legacy of Abraham;

the dust of Arabia turned into a brick in the wall of the Church,”

Khizr comments on the tactful subjugation of the Middle East by

the British by pitting the Arabs against the Turks. “The

tulip-colored cap [a reference to the traditional Turkish fez]

earned a bad reputation in the world, and those who were used

to be coy and vain are now forced to beg and borrow [apparently

referring to the negotiations between the Ottoman Sultan and the

Allied conquerors over a humiliating treaty]. Iran is buying from

the West, a liquor that will melt the container with its heat

[alluding to the trade treaties between Iran and the Western imperialists];

the stratagem of the West did to the Muslim nation what rust does

to gold and turns it into pieces. The blood of the Muslims is

being taken at the price of water; however, your anxiety is based

on ignorance. Rumi said long ago: whenever an old foundation is

to be resurrected, do you not know that the ancient edifice is

first demolished?”

Iqbal’s advice to the Muslim world was in

stark contrast to the prevalent trends of those days, represented

by the Ali Brothers (the larger than life Mualana Muhammad Ali

Jauhar and his high-spirited brother Maulana Shaukat Ali) and

other leaders of the Khilafat Movement, who, on one hand were

forging alliances with the Hindu community on a rather emotional

foundation, and on the other hand taking deputations to those

very colonial rulers against whom they were struggling at home.

“Let the country slip out of your hands

if it does,” Iqbal had said two years ago in a poem titled

‘The Beggars of the Caliphate.’ “You must not

deviate from the commandments of the Truth!” Now, Iqbal

advised through Khizr that the Muslim countries must unite, regardless

of their political situations, and the message came in the verses

that have since then become proverbial: “The Muslims ought

to unite in order to defend their Holy Shrine; from the banks

of the Nile to the soil of Kashghar” (Eik houn Muslim harem

ki pasbani kay liye/ Neil kay sahil say lay ker tabakhak-i-Kashghar).

He advised the Muslim world to hold its calm and fix its eyes

on the long-term vision, ignoring the emergent opportunities that

seemed expediently attractive but defeated the ultimate goals.

Events in the following years proved that Iqbal,

the alleged dreamer, was correct on every count and the heroic

men of action were wrong in their disagreement with the poet-philosopher.

The uproar in London

‘Asrar-i-Khudi’ was translated

by R. A. Nicholson in 1920, a year before Iqbal recited ‘Khizr

of the Way.’ The English speaking world noticed it at once,

and two years later the ‘Lieutenant Governor of Punjab’

(the Raj jargon for the Governor of Punjab), upon hearing the

name of Iqbal from a foreign journalist, woke up to the need for

raising the native poet to the status of an Indian Knight. In

the meanwhile, the mainstream literary current of the West had

taken an outrage against Iqbal’s philosophy. Whatever the

world might have thought at that time, a fresh reading of those

reviews stir our sympathy for Iqbal as a giant stranded among

pygmies.

To begin with, the well-meaning Nicholson

had an unfortunate gift for grasping details with penetrating

understanding while missing out the larger picture even if it

were thrust under his nose. Prior to the publication of his translation

he asked Iqbal for a summary statement, which the poet-philosopher

hurriedly drew up.

“The idea of personality gives us a standard

of value: it settles the problem of good and evil,” Iqbal

wrote in his notes for Nicholson. “That which fortifies

personality is good, that which weakens it is bad. Art, religion,

and ethics must be judged from the stand-point of personality…”

Nicholson, despite the benefit of Iqbal’s complete statement

(which ran into several pages), had the adamant capability of

presenting him as “a religious enthusiast, inspired by the

vision of a New Mecca [sic. Makkah], a world-wide, theocratic,

Utopian state in which all Moslems, no longer divided by the barriers

of race and country, shall be one… It must be observed that

when he speaks of religion he always means Islam. Non-Muslims

are simply unbelievers, and (in theory, at any rate) the jihad

is justifiable, provided that it is waged ‘for God’s

sake alone.’” Iqbal should have been thankful that

this “introduction” to his philosophy was followed

up by an offer of knighthood from the Governor and not by a call

from the Inspector General of CID.

Leslie Dickinson, an acquaintance from Cambridge

who had tried to draw similarities between William Blake and Oriental

sages for Iqbal’s benefit in those days, was quick to take

alarm. “Quite clearly Mr. Iqbal desires and looks forward

to a Holy War, and that too a war of arms,” Dickinson wrote

in The Nation, London, and lamented that weary of a Great War,

the West was now looking towards the East to look for a new star

but what they find there is “not the star of Bethlehem,

but this blood-red planet” (apparently this was an allusion

to Yeats’ latest poem, ‘The Second Coming’).

“The East, if it arms, may indeed end by conquering the

West but if so, it will conquer no salvation for mankind,”

he concluded. “The old bloody duel will swing backwards

and forwards across the distracted and tortured world… Is

this really Mr. Iqbal’s last word?”

Dickinson’s “et tu Brutus, then fall

Caesar” feeling was coming from the fact that the optimists

in Europe at the end of the Great War had begun to hope that there

would not be any more wars, especially since the establishing

of the League of Nations (of which Dickinson was one of the pioneers).

Iqbal, as much as he might have desired peace, was under no illusions:

to him, the League of Nations was a rendezvous of coffin thieves

for distribution of graves. He wrote to Nicholson and asked him

to pass on the message, “Mr. Dickinson… is quite right

when he says that war is destructive, whether it is waged in the

name of truth and justice, or in the interests of conquest and

exploitation. It must be put an end to in any case. We have seen,

however, that Treaties, Leagues, Arbitrations and Conferences

cannot put an end to it. Even if we secure these in a more effective

manner than before, ambitious nations will substitute more peaceful

forms of the exploitation of races supposed to be less favored

or less civilized. The truth is that we stand in need of a living

personality to solve our social problems, to settle our disputes,

and to place international morality on a sure basis…”

Iqbal looked forward to the possibility that the

evolution of civilization may one day outgrow war and conflict,

but, he added, “I confess, I am not an idealist in this

matter and believe this time to be very distant. I am afraid mankind

will not for a very long time to come, learn the lesson that the

Great European War has taught them.”

Dickinson had also complained that Iqbal applied

his universal philosophy only to a particular nation while the

non-Muslims were kept out of the promised kingdom. Replying to

this, Iqbal pointed out that universal humanitarian ideals need

to be started with a group of like-minded people when it comes

to putting them into action. While it was not his purpose to make

a case for Islam at all, he had still chosen to start with the

Muslim society because “it has so far proved itself a more

successful opponent of the race idea which is probably the hardest

barrier in the way of the humanitarian ideal… Tribal or

national organizations on the lines of race or territory are only

temporary phases in the unfoldment of collective life, and as

such I have no quarrel with them; but I condemn them in the strongest

possible terms when they are regarded as the ultimate expression

of the life of mankind.” It might have been very difficult

to grasp the full significance of his statement in those days

but it is perhaps easier to do so today when the natural course

of human development has presented us with the phrase, “the

global village.”

The unkindest cut of all came from none other than

the novelist E. M. Forster (whose Passage to India was still in

the making and would appear two years later). Reviewing Nicholson’s

translation in The Athenaeum, he lamented the fact that Iqbal

had not been translated earlier, unlike Tagore. The natural genius

of Forster enabled him to make a profound observation: “Tagore

was little noticed outside Bengal until he went to Europe and

gained the Nobel Prize, whereas Iqbal has won his vast kingdom

[among his own people] without help from the West.” This

compliment was truer to the characteristic self-respect of Iqbal

than any from his own people. However, Forster was a blind visionary

and he anachronistically placed the so-called “nationalist”

poems of the Bhati Gate period as Iqbal’s latest; his understanding

was that the poet, after writing Islamic poetry, changed his position

to join the mainstream Indian liberation movements and was now

coming close to the vision of a homogenous Indian nation!

Through this same fatal review, the kind and well-meaning

Forster inadvertently reinforced the misunderstanding originally

made by Nicholson and subsequently picked up by every reviewer:

Nietzsche’s alleged influence on Iqbal. However, Forster

went a step further than the rest. “The significance of

Iqbal is not that he holds [the doctrine of Nietzsche] but that

he manages to connect it with the Koran. Two modifications, and

only two, have to be made…”

One can only imagine how Iqbal must have felt at

reading this. “[The writer in the Athenaeum does not] rightly

understand my idea of the Perfect Man which he confounds with

the German thinker’s Superman,” he complained to Nicholson,

“I wrote on the Sufi doctrine of the Perfect Man more than

twenty years ago, long before I had read or heard anything of

Nietzsche…” He went on to quote the date of publication

of his Al-Jili thesis and also hoped that if the reviewer “had

known some of the dates of my Urdu poems referred to in his review,

he would have certainly taken a totally different view of the

growth of my literary activity.” Frankly, we cannot be so

sure of that. Firstly, Forster was in a habit of mugging up his

facts – in another article, years after Iqbal’s death,

he attributed to Iqbal not only poems in Urdu and Persian but

also in Punjabi! Secondly, Forster was diametrically opposed to

Iqbal in his beliefs about art and literature, and Iqbal should

not have hoped for any good from him despite the best intentions.

A Passage to India is generally hailed

as Forster’s humanitarian outcry against racism, and therefore

the mischief of that book has gone unnoticed: why are the best

examples of personalities from both sides – the native as

well as the British – absent in that book? This pathetic

piece of self-deprecating guilt originated a long line of writings

in which the sub-continent is presented as home to pitiable creatures

tormented by the advances of a cruel modernism, and this tradition

has come down to our own times in many presumed masterpieces.

Long time ago, Iqbal had made a prediction about

the future of Western literature but kept it to himself; in 1920

he must have begun to realize that his prophecy had come true

with more accuracy than he could grant it. “By the time

I arrived in England in 1905, I had come to feel that despite

its seeming beauty and attraction, the Oriental literature was

devoid of a spirit that could bring hope, courage and boldness,”

Iqbal stated at one point. “Looking at the Western literature

[while in Europe], I found it quite uplifting but there, the science

was poised against humanities and infusing pessimism into it.

The Western literary situation was no better than the Oriental

in my eyes by the time I returned in 1908.”

With uncanny prophetic accuracy, the last Romantic

foresaw the dawn of an age when loss of pride in the human soul

would manifest itself in all walks of life in Europe – through

fascism, Nazism and tyranny of the masses in politics; through

an obsession with exploring mental diseases without defining mental

health in psychology; and in art through disintegration of form

itself and an aversion to beauty (form, according to Iqbal, was

important for the existence of the ego, and he defined it as “some

kind of local reference or empirical background”).

In the aftermath of abundant reviews on his poem

in the British literary circles (and perhaps also alarmed at their

intellectual deficiencies), he decided to give a helping hand

to the West. His next work was going to be addressed to the Europeans.

Payam-i-Mashriq, or The Message of the East!

Previous

| Contents | Next

|